HEIDI YARDLEY

BIOGRAPHY

Melbourne based Heidi Yardley completed a BFA at Monash University (1995) and Honours at RMIT (1999) and is currently undertaking a PhD at Curtin University. She has been a finalist in significant Australian prizes including The Archibald Prize (2016, 2014, 2013), The Wynne Prize (2016) Sulman Prize (2014) the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize (2013, 2011, 2009), the Hazelhurst Art on Paper Award (2019), the National Works on Paper Prize, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery( 2020), the Paul Guest Prize, Bendigo Art Gallery (2020) and the Percival Portrait Painting Prize, Perc Tucker Regional Gallery (2020).

Heidi Yardley has been included in curated group exhibitions throughout Australia. She has held two artist residencies in New York funded by the Ian Potter Cultural Trust (2011, 2014) and has been listed as one of Australia’s 50 most collectable artists (Australian Art Collector magazine, 2011).

Heidi Yardley’s work is held in public collections including Artbank, Gippsland Art Gallery, Ballarat Art Gallery and the University of Queensland Art Museum.

ARTIST CV

DOWNLOAD PDF

WORKS

CONTACT GALLERY FOR PRICE INFORMATION

PAST EXHIBITIONS

GLITTERED IN THE CAVE

16 MARCH TO 2 APRIL 2022

SATIATING DESIRE

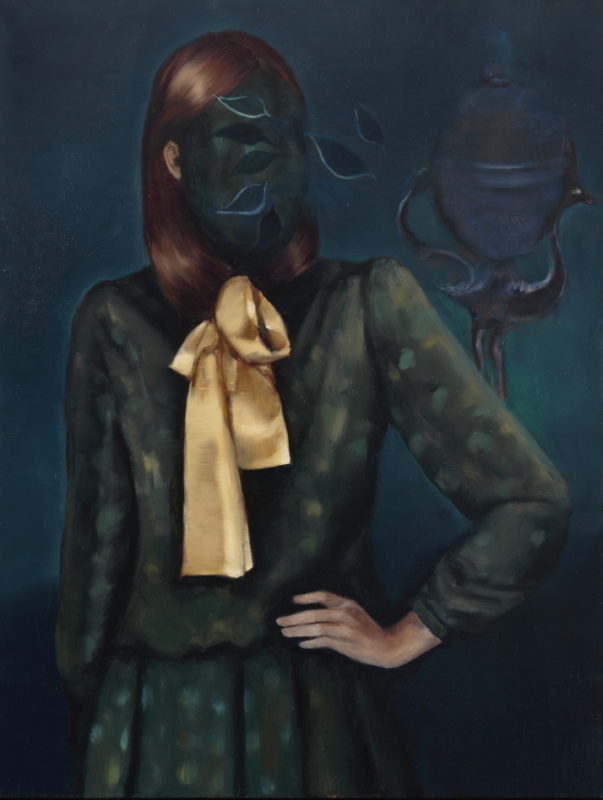

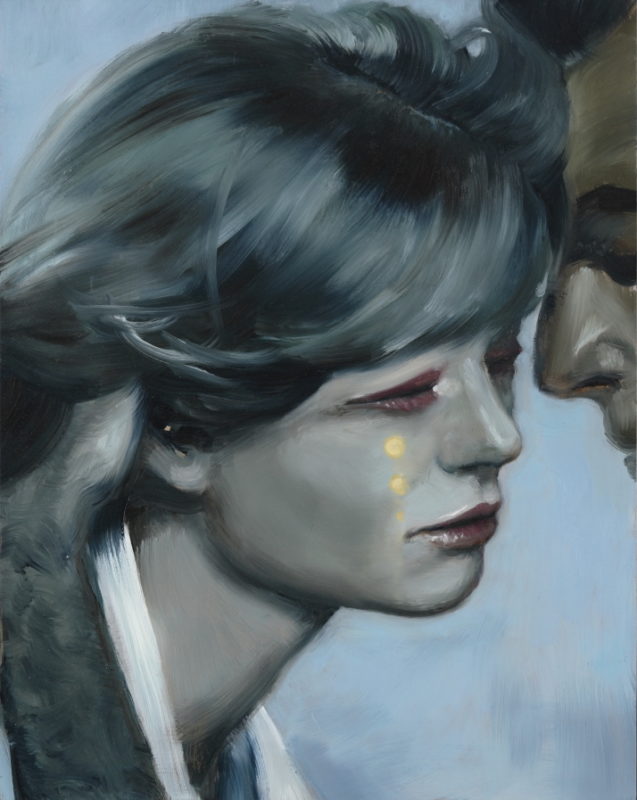

In the works of Heidi Yardley, enigmatic subjects wrestle with inner worlds.

Heidi Yardley has a thing for tarnished glamour. Not the glowing perfection of the digitally enhanced promotional shoot or the golden age of Hollywood, but the tell-tale signs of the body leaking through the glossy veneer. In her oil paintings of female figures, closely cropped in various interiors, this is reflected in part in the muddy tones she is inevitably drawn to, adulterated colours that recall the print technologies of 1970s magazines. This is no coincidence, as Yardley collects books, catalogues, and magazines from this time, using them as analogue source material for the collages she then scans and modifies before transforming through paint. She admits a certain romantic soft spot for the 70s, the decade of her birth, when her family was still together and her mother was in her prime: she was a big fan of proto-feminist movie stars like Jane Fonda and Brigitte Bardot and shared that passion with her daughter. Alongside her mother’s accumulated paraphernalia, Yardley also collects the classic soft porn of the era, Penthouse and Playboy, whose cheesecake centrefolds she reimagines as shrouded, enigmatic subjects wrestling with their inner worlds.

Yardley has observed the continual incursions of her matriarchal heritage in her current painting series, as she processes her recent bereavement. An example is the figure in The colours of Chloe, 2021, scanned from one of the luscious film catalogues her mother had kept from the original screening many decades prior. Another is a childhood object of fascination, her mother’s fox stole, that appears in Foxtrot, 2021: it lies slack in one corner of the composition but resonates in the swirl of caramel fur that obscures the slim, fashionable woman’s face.

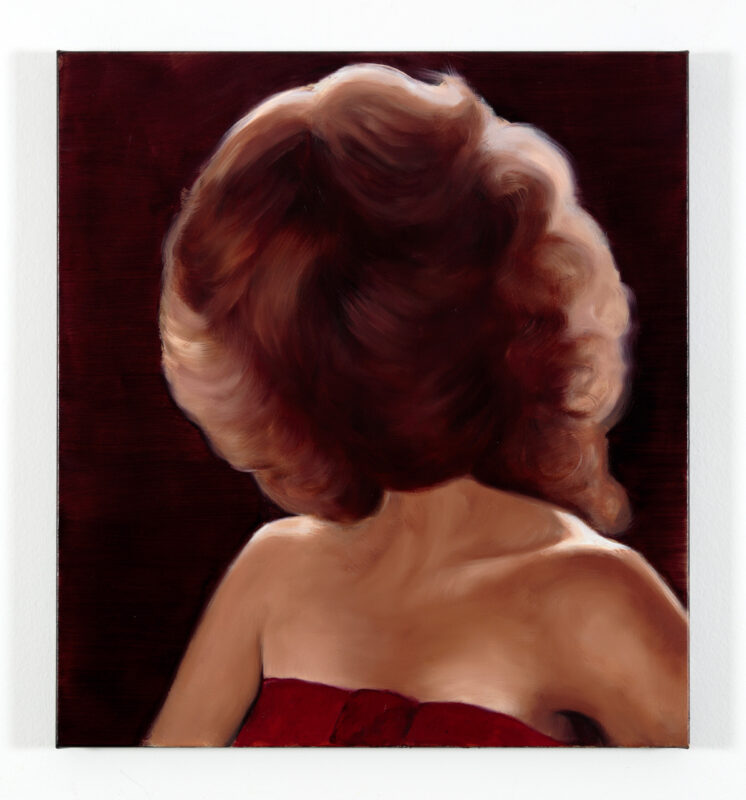

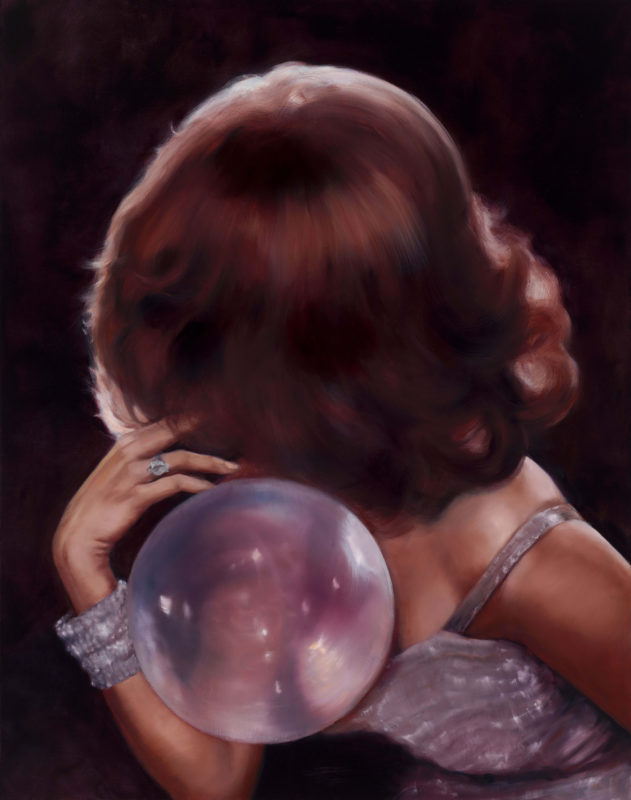

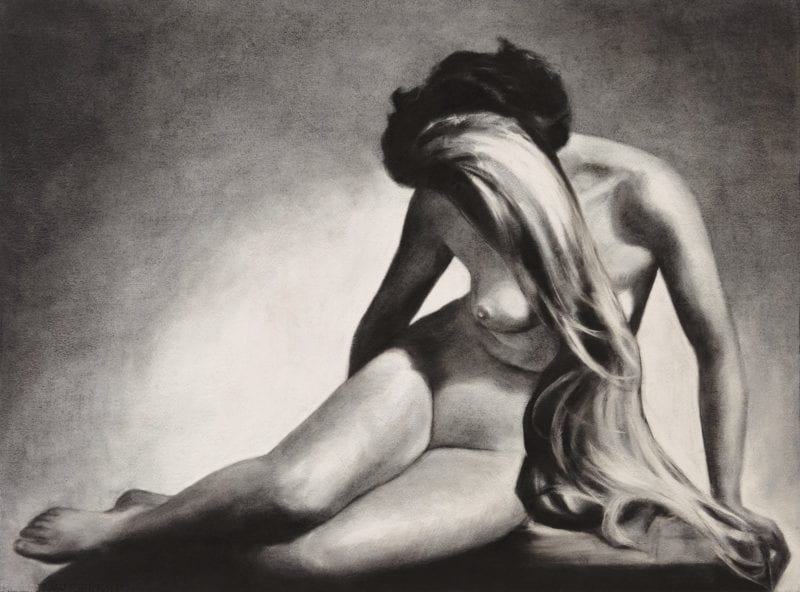

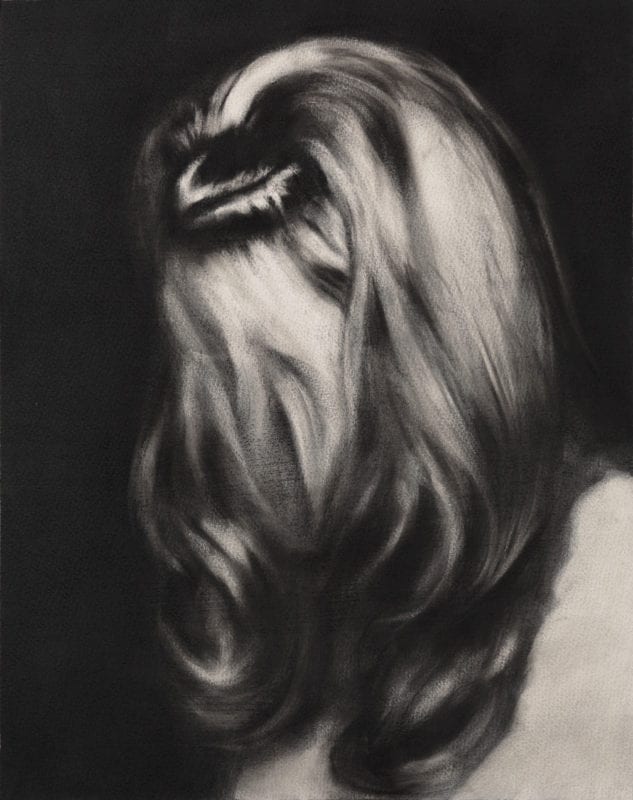

A swatch of fur also covers the sitter’s eyes and breasts in Chloe, 2021, while flowing black, brunette or copper hair stands in for the faces of the figures in the other works. Yardley is seduced by the liquidity of hair and fur, and clearly relishes the process of rendering these enticingly tactile materials in paint. The paintings draw us in to touch, but the slightly sickly palette and the psychological intensity of the figures combine to ward us off, rendering us intruders into intimacies beyond our understanding.

Fur and hair are, of course, loaded signifiers, particularly when meshed with the female form. Yardley plays with these long-standing associations – sexuality, animality, fetishism, memento mori – well-aware of her debt to the Surrealists, in particular the women who complicate the misogynist stereotypes associated with the movement.

In the paintings of Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning, for example, hair serves to assert personal power or open a portal to another psychic dimension. Toyen and Kay Sage veil the faces of their female subjects with hair so that their crowning glory becomes less object of the gaze than affirmation of self-satisfied desire.

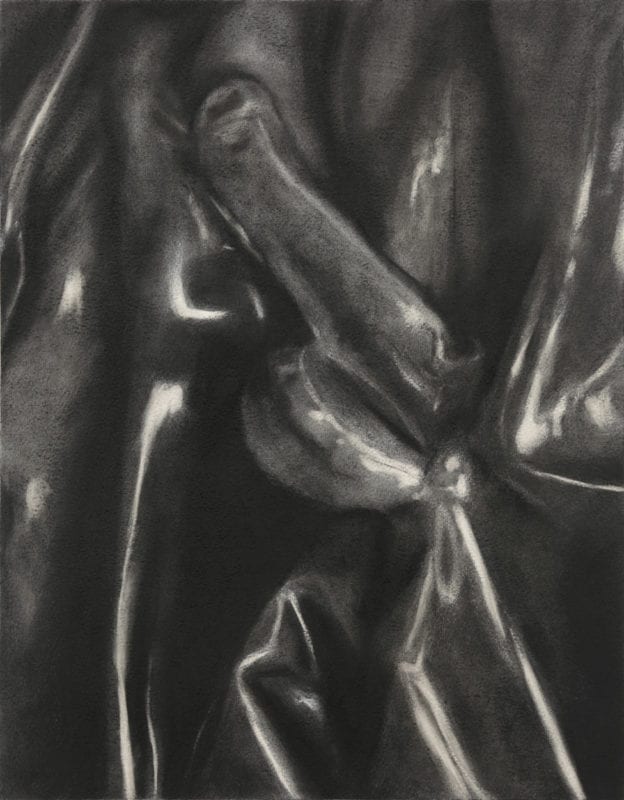

Yardley’s extraordinary Femme en Fourrure is a direct homage to the quintessential Surrealist object, Meret Oppenheim’s fur teacup. This larger-than-life painting of a fur coat, with its heavy folds and undulations coupled with phallic architectural touches, is delightfully excessive, perfectly bringing together the artist’s concerns: nostalgia and secrets, female sexuality and the veneer of glamour, and the materiality and pleasure of the painting process.

Jacqueline Millner for Art Collector

THE THIN VEIL

22 MAY TO 9 JUNE 2019

EXHIBITION PRESS

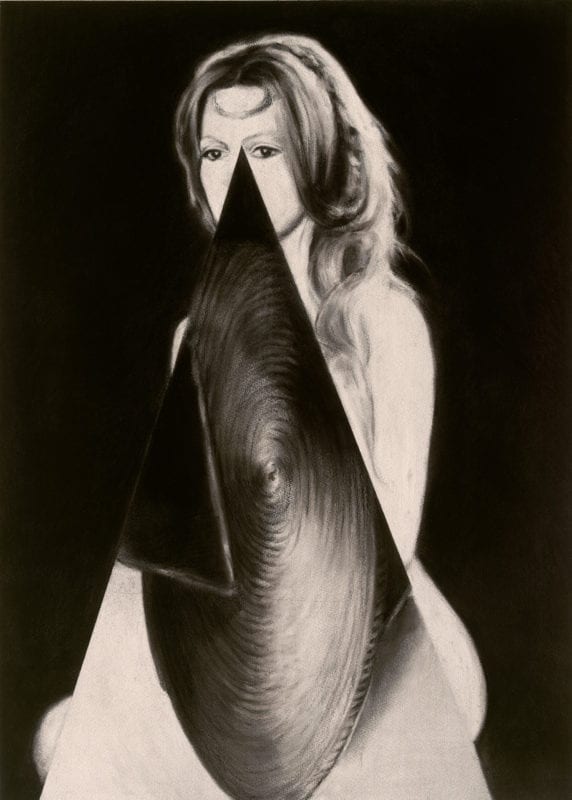

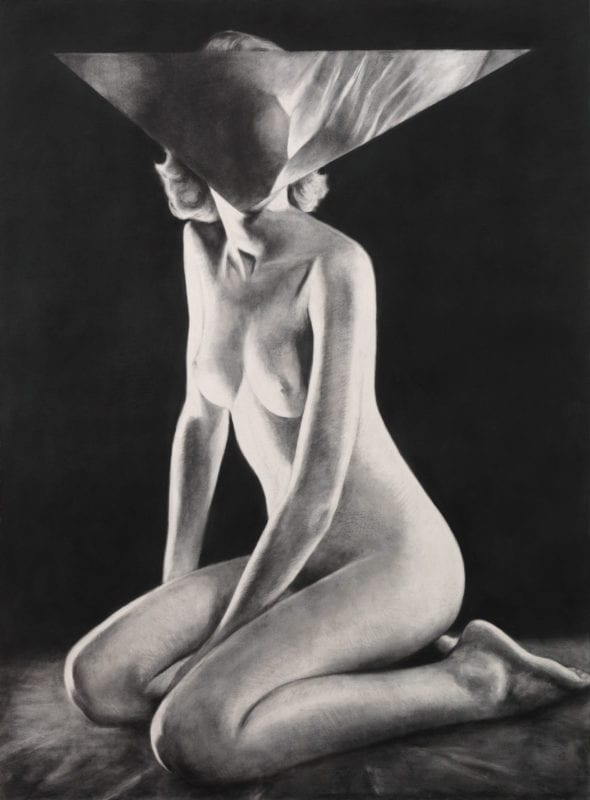

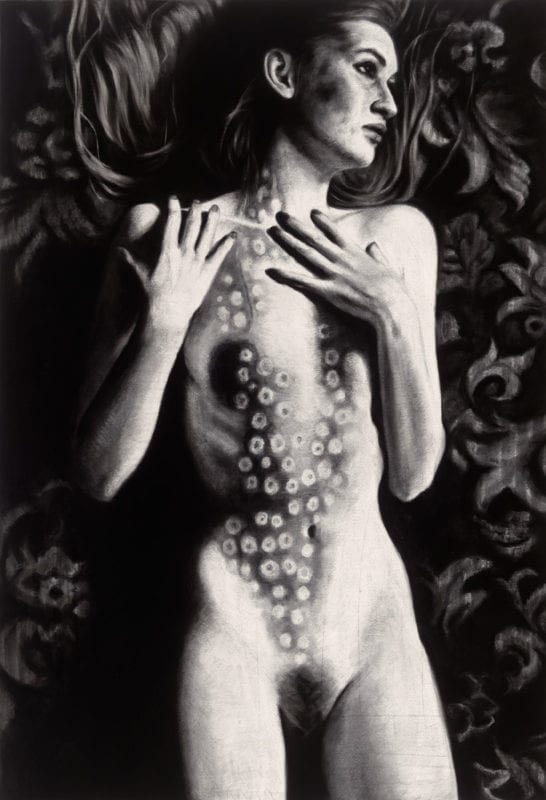

...In The Thin Veil (2019), a naked woman kneels expectantly, her soft flesh illuminated by a stark spotlight. Yet this seductive sexuality is ruptured by the triangular shard veneering her face, its razor-sharp edges daring the voyeur/viewer to approach. Can you elaborate on this work?

I’m trying to represent an idea of other dimensions that exist outside of our own awareness. The title refers to the 'thin veil' between the living and the dead, a spiritual concept that other dimensions are not far from our own. Playing around with collage led to this particular image and it made me think of the film ‘Metropolis’ (1927), even though I can't recall the last time I saw that film. There's something futuristic about the triangular shard and the central part reminds me of a fencing mask. So protection is also a part of the idea behind the work.

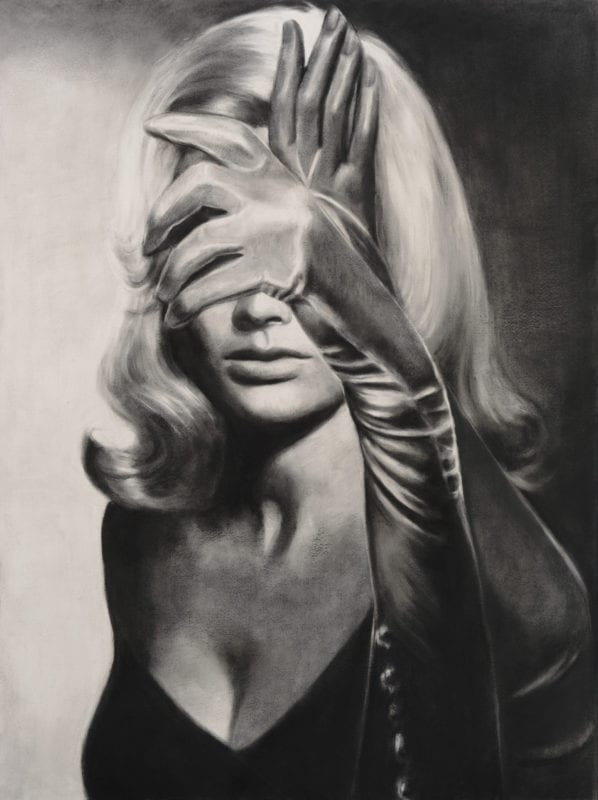

The elegant gloved hand in Rechannelled (2019) smothers the figure’s face in a gesture that feels both affectionate and aggressive. What’s happening in this work?

This work is about the loss of my mother, who died just over a year ago. It feels like someone being stolen from you, so I used the mysterious gloved hands to disguise the identity of the face. The image of the woman is not directly from a photo of my mother, but it looks very much the way she did in photographs from the 1960s before I was born. Death is inevitable for everyone but it doesn't seem to provide answers, only more questions. It's difficult subject matter for me but seems to be part of my grieving process.

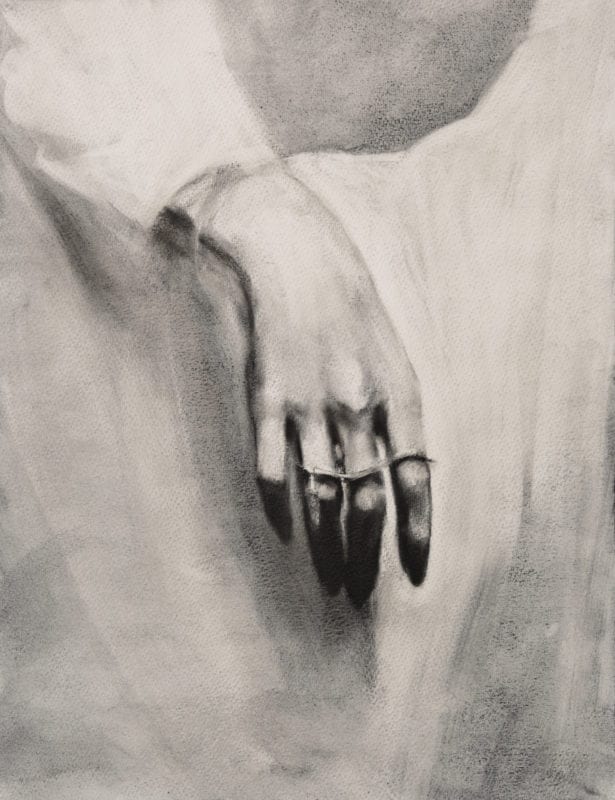

The trope of hands seems to feature heavily in your latest series…

I'm particularly interested in hands at the moment as a symbol of connecting to the afterlife. I'm fascinated by gestures of connection, kindness and longing. In Symbolic terms for example, the right hand can represent the rational, conscious and logical mind while the left can symbolise weakness, decay and death. Then there's terminology such as 'Hand in glove' which refers to a very close relationship or agreement. Early tribal cave paintings show hand prints that seem to have been made in order to communicate a message to other tribes and very possibly to reference a communication with ancestors who had passed. There is so much more to the Symbolic nature of the hand in history and art...

extract from interview with Elli Walsh for forthcoming Artist Profile issue 47

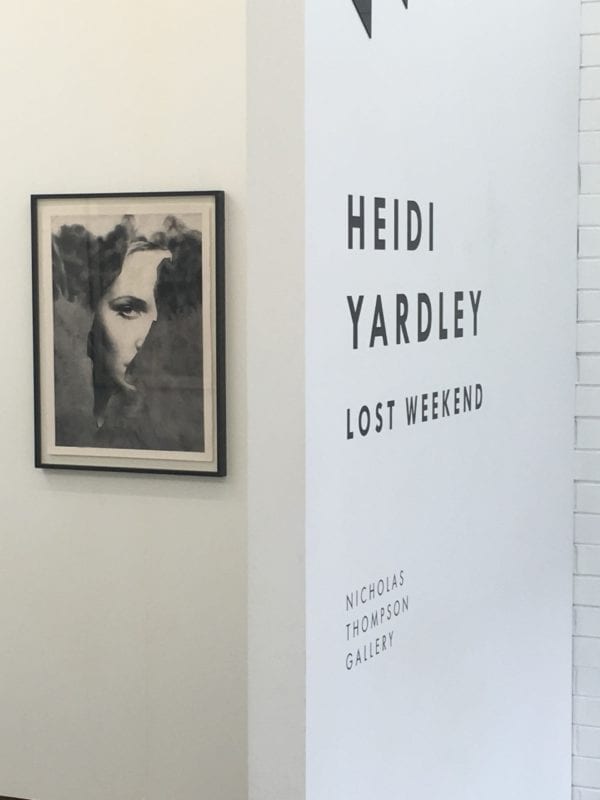

LOST WEEKEND

16 TO 27 AUGUST 2016 - EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY AT NEOSPACE, COLLINGWOOD

Heidi Yardley’s Cadavre Exquis

“… the association of two, or more, apparently alien elements on a plane alien to both is the most potent ignition of poetry.”

– Comte de Lautréamont, Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869

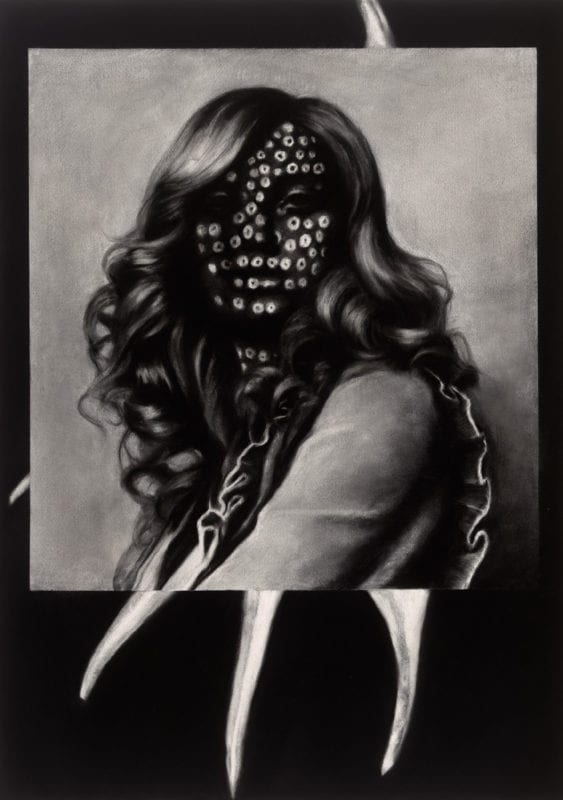

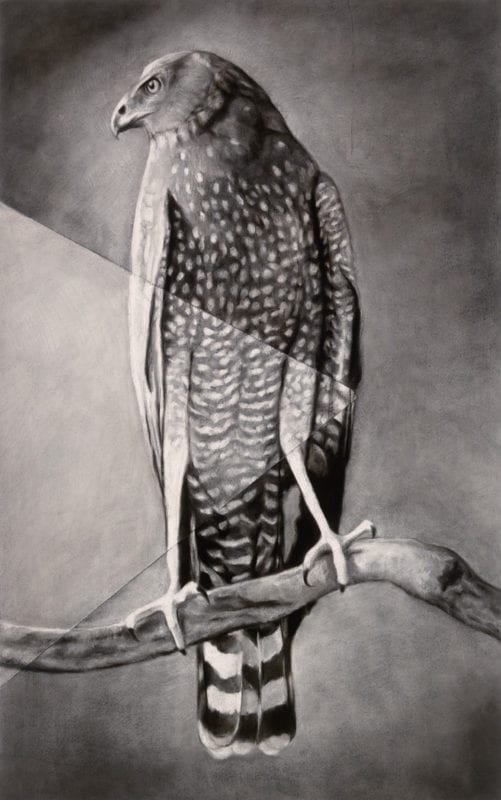

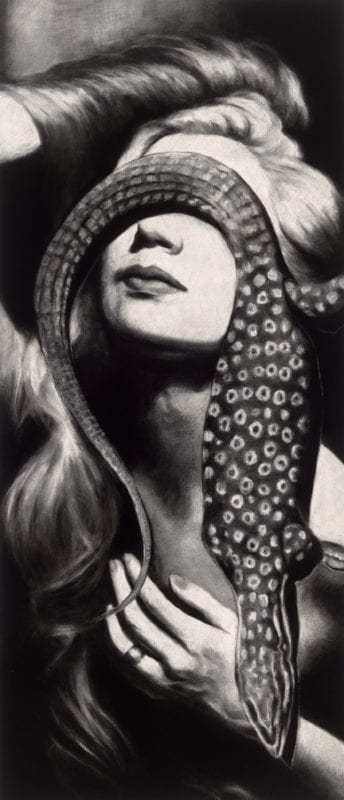

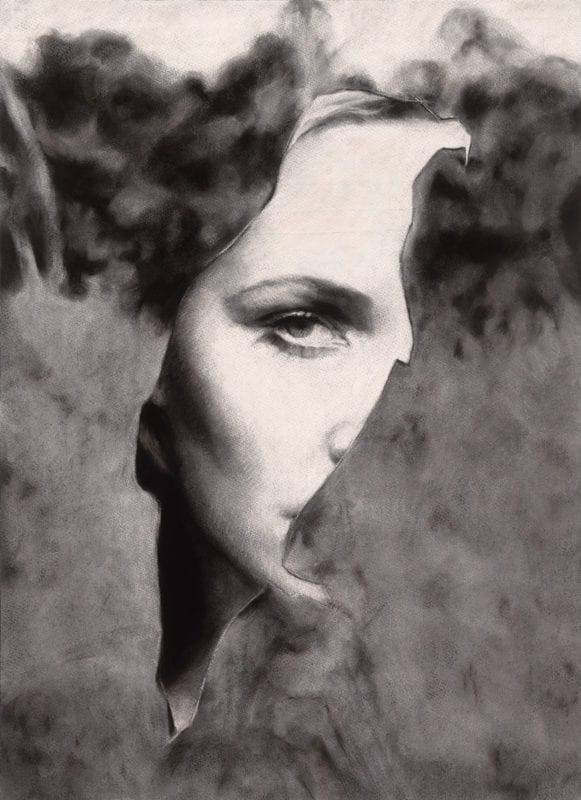

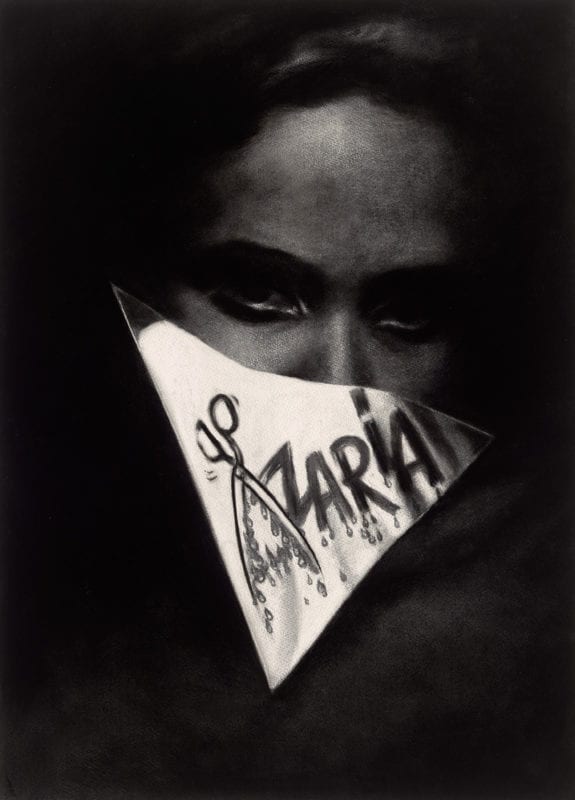

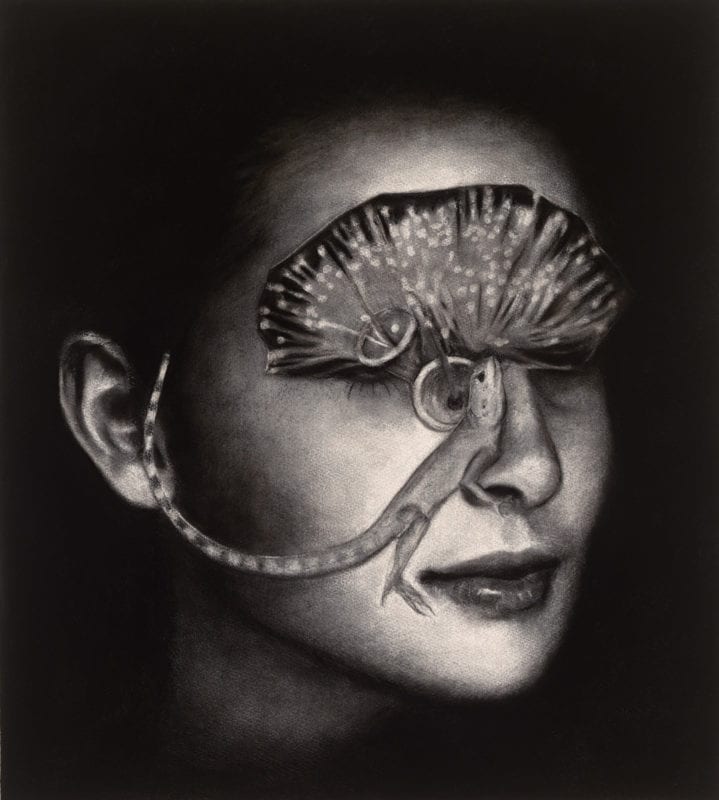

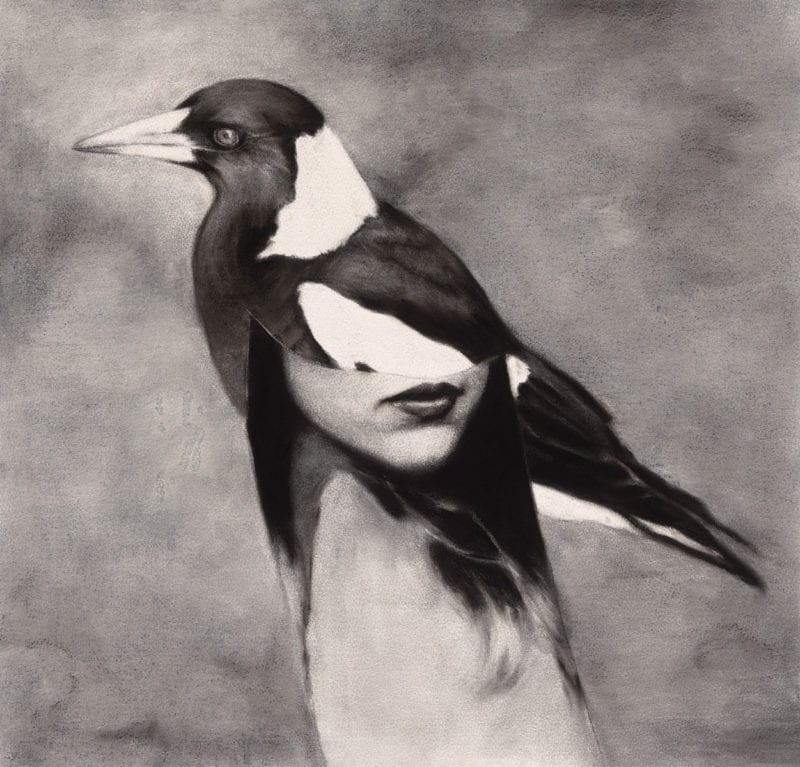

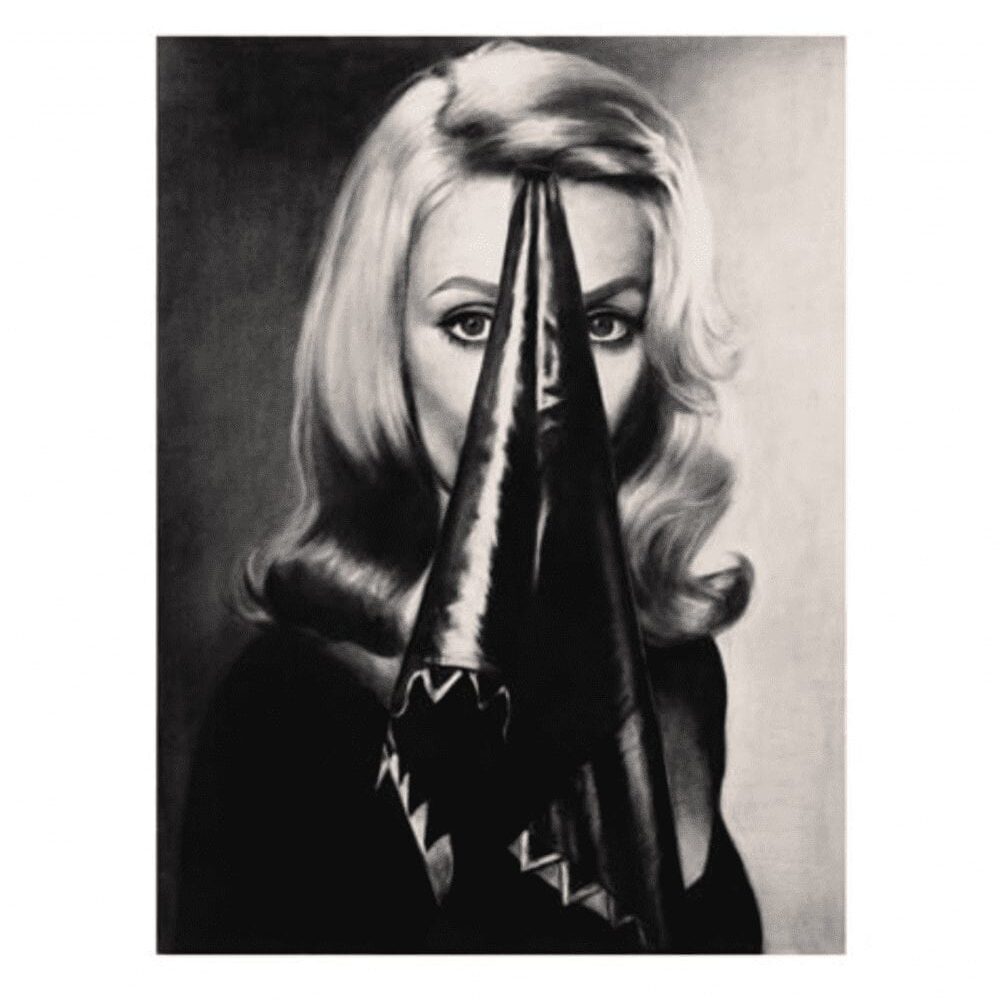

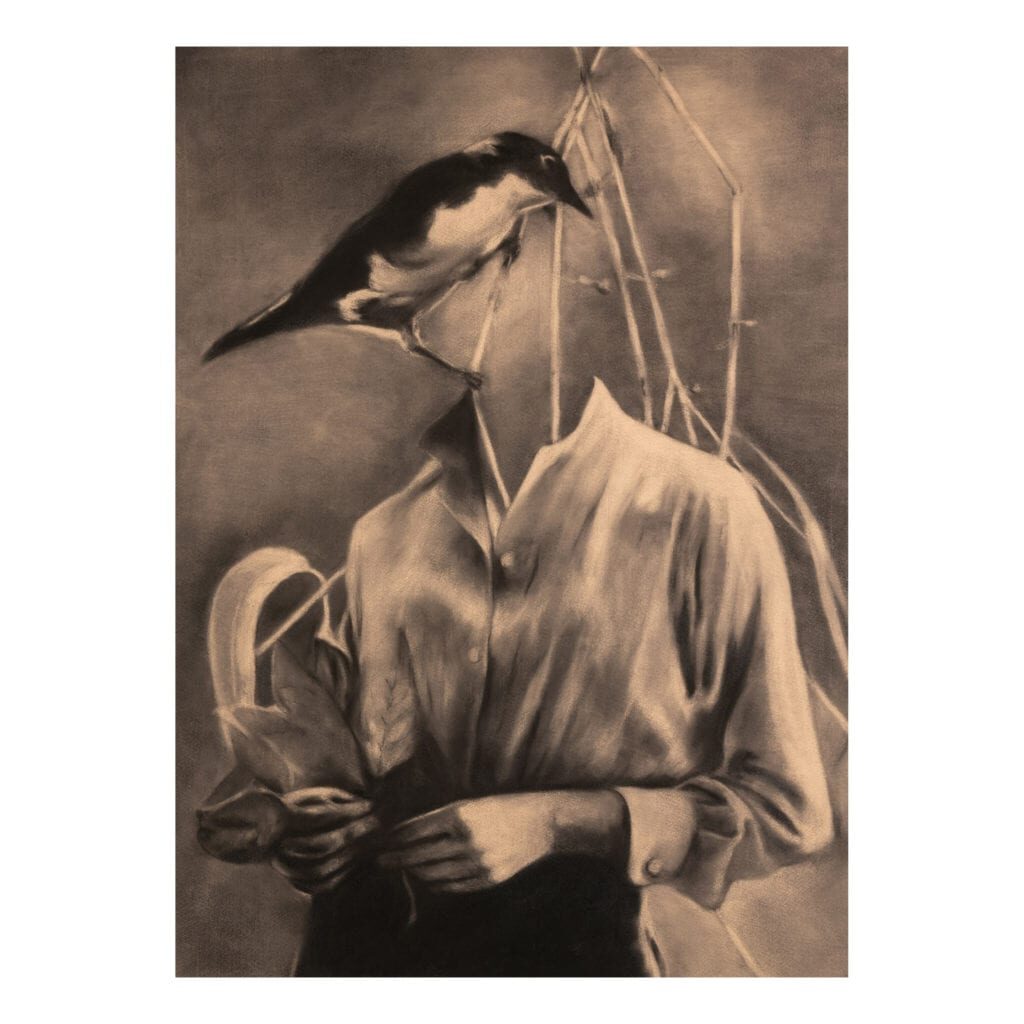

Heidi Yardley’s latest works inspire burning questions. Her animal-human hybrids could see her feminine protagonists embracing nature with an almost bizarre passion. Alternatively these could be fashion models adorning the latest feathery and scaly accouterments. Another possibility may be that these women have suffered strange environmental mutations. One thing is without doubt; they wear their birds and lizards whilst retaining a sultry sensuality. But one wonders – are they wearing their animals or are the animals wearing them?

There have always been forms of animal-human splicing. Tribal warriors in various parts of the globe adorn themselves with feathers to inspire fear and respect and to attract the attention of women. Women, meanwhile, have adorned feathers and furs to attract the attention of men. There is a long and magical history of human/animal interface. Consider the legends of Marsyus and Pan. The Greek Centaur and the Japanese Kitsune, or Anubis, the Egyptian God of the Dead with his head that of a jackal. And then there are the more contemporaneous versions of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, David Cronenberg’s The Fly and Charles Burns’ Black Hole, amongst others.

Heidi Yardley’s ladies of the night are, I like to imagine, adorned to partake in a lavish party, patiently waiting for the artist to capture their likeness in charcoal, thus to be remembered in their painful but beautiful melding with the natural world. Perhaps they have gone to extremes to attend the immensely wealthy Marie-Hélène de Rothschild’s famous Surrealist Ball at Ferrières, which was held on December 12, 1972 and attended by the likes of Audrey Hepburn and Salvador Dalí. The requirements for the evening were “Black tie, long dresses & Surrealists heads.”

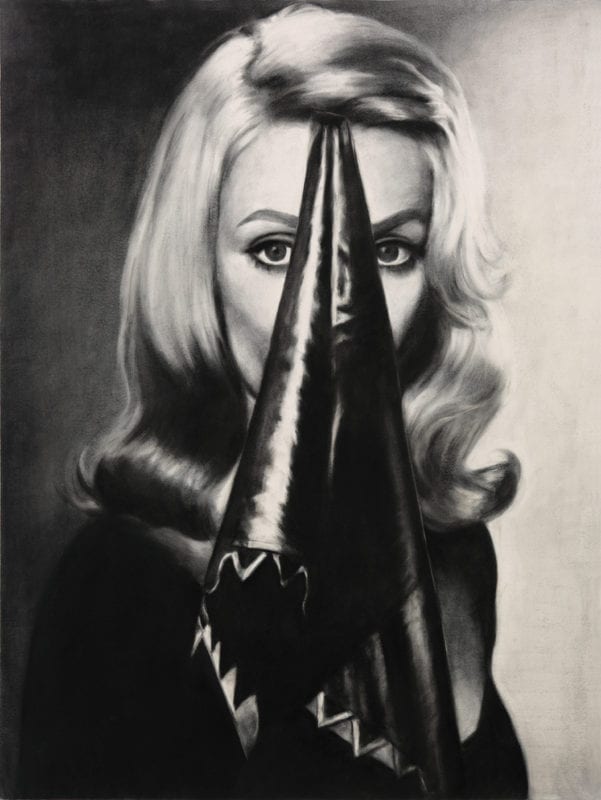

Yardley takes these notions of animal/human interface to new extremes, introducing an element of sheer seduction into the proceedings. There is the almost inevitably sultry glamour of the artists’ renderings of women – see By the danger in your eyes – and her embrace of a distinctly ‘retro’ style (the artist has at times utilised imagery from early 1970s porn, a time when the plumage of pubic hair was de rigueur.) Filmic sources and magazine photography have long played a role in Yardley’s work, both as a source and an inspiration. Her title, Lost Weekend, is in fact a play on the film title Long Weekend (1977), ostensibly a horror flick about nature’s revenge on a man treating the bush with contempt. By a quirk of fate the gallery’s director, Nicholas Thompson, had misread Yardley’s handwriting, interpreting “Long” for “Lost,” thus accidently, but aptly, renaming the artists’ show, much to Yardley’s delight. This was also, fittingly, a form of Cut-Up or Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse) – the collaborative poetry game that has its roots in the Parisian Surrealist Movement and involved such participants as André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Yves Tanguy, André Breton, Man Ray and Tristan Tzara. While it began as a form of Chinese Whispers with surreal word usage (later inspiring William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up method) it rapidly evolved into a more visual series of collaborations. With Yardley’s approach, with its cut-and-paste technique, in this case a montage of nature photography and fashion imagery, which is then rendered masterfully in charcoal, something not dissimilar occurs, the juxtaposing elements initially jarring until settling into a form of poetry.

Yardley has long been the master of melding beauty and threat. “This series investigates the relationship between the natural environment and the human psyche, particularly focusing on notions of fear,” she says of Lost Weekend. The allusion to the fabled Azaria drama in Shake dog shake aside, these fears are not entirely unfounded; I was once asked to travel with a Japanese artist through Australia’s centre. I had warned him about making noise to scare away snakes when undertaking his ablutions. He learnt that trick, only to find himself squatting one day over a bull ant nest. Another lesson was learnt… the hard way.

“Lurking within the common consciousness of Australian identity is a fear of dangerous wild animals and the treacherous natural environment,” says Yardley. “These hybrid images speak of connection and disconnection, primal urges, desire and fear.” Indeed, fear and beauty reside in equal measure in these works. She melds two forms of exquisite visage – the glamorous femme fatale and the exotic plumage and sensual squamous scales of Australian wildlife to create hybrid life-forms both alluring and threatening.

The sumptuous sense of nostalgic fashion photography is captured via Yarley’s almost photo-realist use of monochrome a la Max Dupain and her elegant placement of her “models” as they show off their accouterments. In The Crown this takes the form of a cockatoo’s plumage, in Missing our subject has adopted snake skin and in Sombre Reptiles her appurtenances take on the form of an entire lizard as facial wear. But it is with Butcherbird that our original speculation returns. Are they wearing the wildlife? Or is the wildlife wearing them.

– Ashley Crawford

NEWS

HEIDI YARDLEY FINALIST IN THE ‘2020 NATIONAL WORKS ON PAPER’ AT MORNINGTON PENINSULA REGIONAL GALLERY, CURRENT 5 DEC 2020 TO 21 FEB 2021

Heidi Yardley ‘Strangers to ourselves’ 2020 charcoal on primed paper 76 x 56cm The Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery’s National Works on Paper was established in 1998 and incorporated the former Spring Festival of Drawing and the Prints Acquisitive which began in 1973. MPRG will hold the prestigious 2020 National Works on Paper (NWOP) acquisitive exhibition from 5…

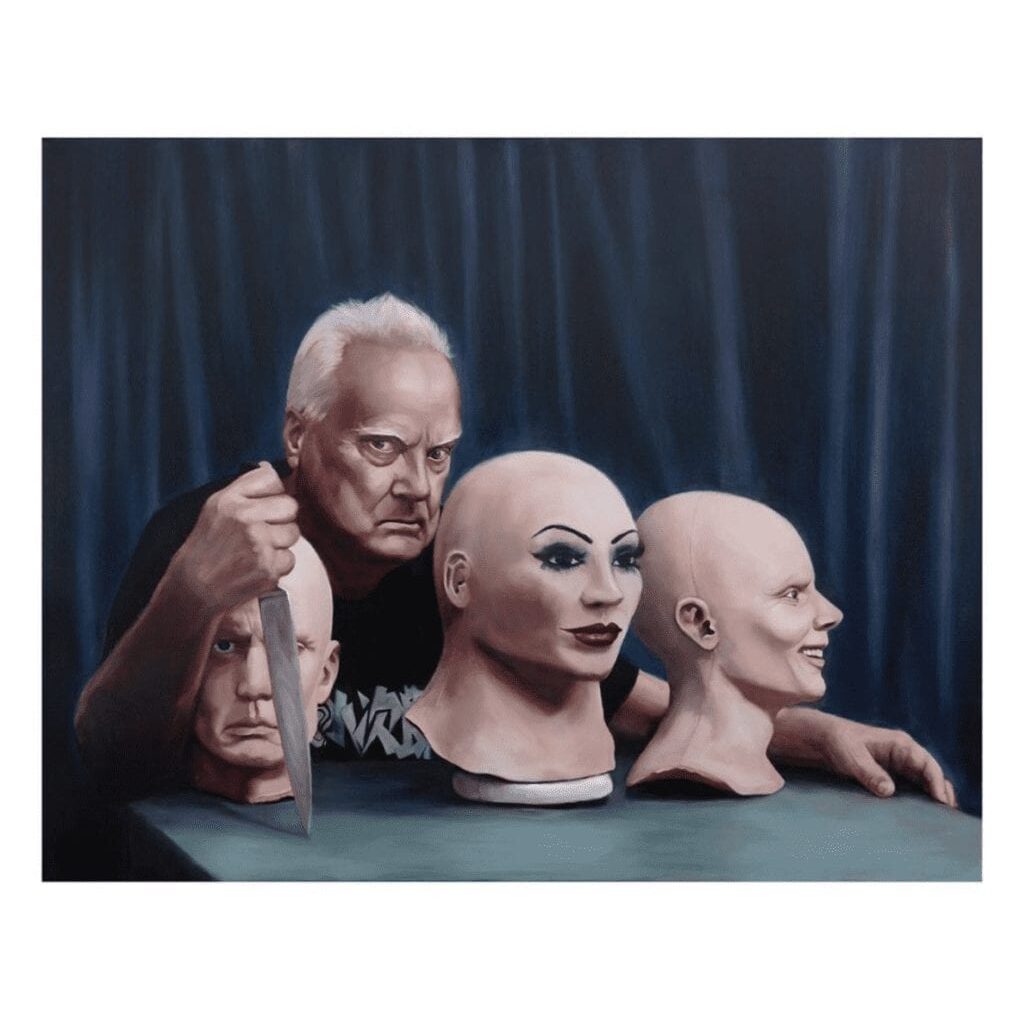

HEIDI YARDLEY FINALIST IN THE 2020 PERCIVAL PAINTING PRIZE AT PERC TUCKER REGIONAL GALLERY FROM 22 MAY TO 19 JULY WITH HER WORK ‘GARETH SANSOM – GRAND GUIGNOL’

- « Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next »