SUZANNE ARCHER: WE ARE THE STARS (2021)

EXHIBITION ESSAY

Suzanne Archer’s paintings just get better and better. With the rich underpinning of her (nearly) six-decade career, the exhibition We are the stars at Nicholas Thompson Gallery creates a visual sensation for the viewer akin to immersion; a compression between bold canvases experienced with the greatest of delight.1 Archer paints on a grand scale and the three main walls of the gallery are anchored by an almost continuous panorama of macro and micro detail. The effect is electric.

Suzanne Archer in her studio, Wedderburn NSW, 2019. Photograph Riste Andrievski.

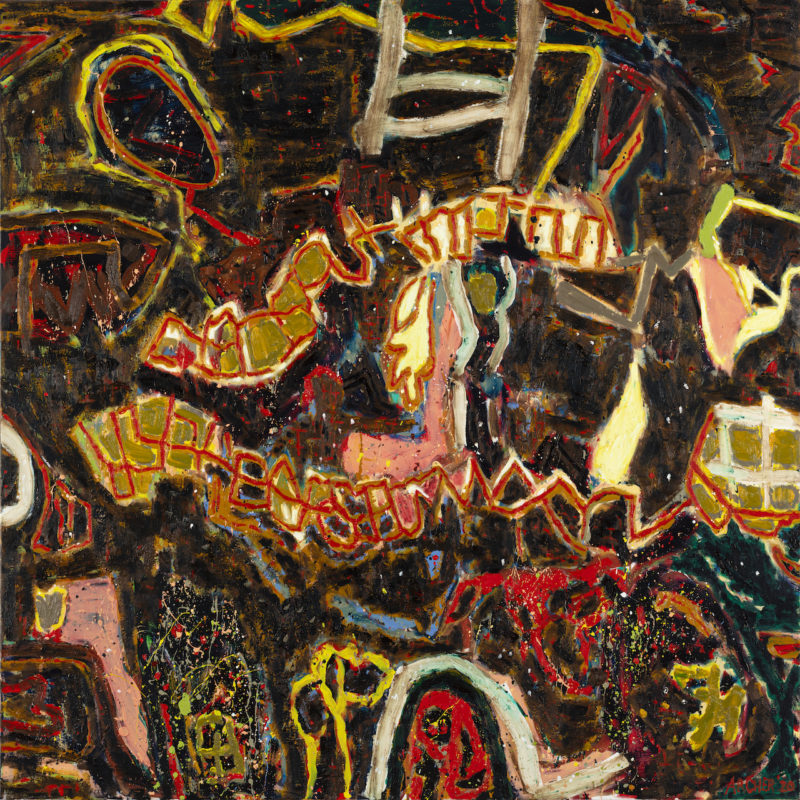

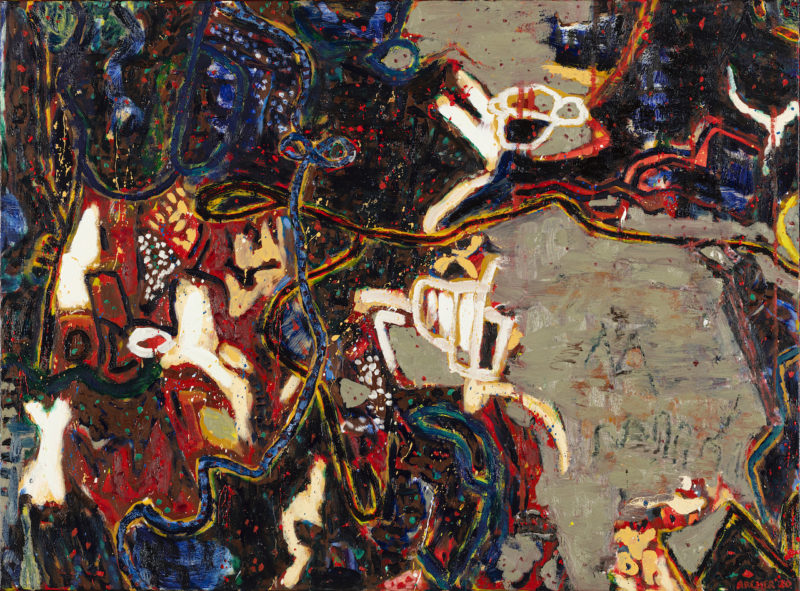

For thirty-three years, Archer has lived in the scrubby forests of Wedderburn, outside Sydney, and it is these lands of the Dharawal people that infiltrate and pulsate within her art. However, hers is not a ‘point and record’ topographical form of landscape, an attempt to create a painterly illusion akin to photography. Instead, Archer wants to record the sensation of being inside a landscape, feeling stones underfoot or leaves as they slash past her face. In a recent podcast, the interviewer noted the lack of horizon line in Archer’s paintings and how this makes the viewer feel embedded within the bush.2 This sensation is further conveyed by the artist’s own language of abstract marks which operate as a form of shorthand to express such visceral experience as touch, smell and heat. For example, in Fledge, 2020, the cross-hatch which animates the surface of the bold red expanse expresses the cracked surface of parched soil in a concisely accurate manner. Similarly, in We are the stars, 2019, the view is celestial but the landscape of the sky is no less vivid, as the night’s black-and-blue flickers with the lush intensity of her expressive brush.

From her earliest days, Archer maintained a love of words and phrases but it is their appearance rather than the precise meaning which inspires her. In Splendour, 2019, the title is roughly inscribed into the surface but is more enquiry than statement. The image was painted during the height of summer and the glaring, white light is all-pervasive. The interspersed patches of soft blue and meandering lines allude to the gullies and sporadic watercourses at Wedderburn but does it truly portray ‘splendour’, or does that refer instead to the scattered feathers of the inverted bird, or rather, its mummified corpse? Archer’s titles should be interpreted as poetic allusions, enigmatic but suggestive. Similar fragmented language was a continuous thread running through Archer’s recent Retrospective Song of the cicada at the Campbelltown Arts Centre (2019), with one installation, Mutter Masks, featuring a soundscape of the artist reading from a sequence of monologues abstracted by the cut-up method pioneered by the Surrealists. Such is her fascination that she also recognises potential written language in nature itself, with the calligraphic marks of the Scribbly Gum (Eucalyptus haemastoma) forming the basis of Glyph 2020.

For Archer, everything remains in a state of flux in a painting until she makes the aesthetic (and emotional) decision as to when the final mark has been applied. This can take weeks but she always pushes herself: ‘I react to the surprise of it, like the surprise of suggested words, ideas.’3 Her studio is a cabinet of curiosities, containing skeletons, shells, seedpods, and snakes in jars scattered amongst her paintings, and images cut out of magazines and previous paintings pinned to the wall. The mask at the centre of We are the stars, 2019, for example, is one of the latter, and only ‘arrived’ in the painting toward the end, a spontaneous inclusion that completed the composition both as anchor and disruption. A similar occurrence is the floating shopping bag (one of the Mutter Masks) that haunts Archer’s entry in this year’s Sir John Sulman Prize, Winterburn, 2019.

A recent appearance in Archer’s paintings – somewhat inevitably – is the now-ubiquitous medical mask but its inclusion is not for the health message; rather it is the structural form of the covering, its potential as an abstracted motif that excites the artist rather than any didactic lecture. These masks punctuate the field in Seclusion 2021, and Windblown 2021, with the three examples in Windblown reduced to such an elemental outline that they invoke animal forms carved by Indigenous Australians. By contrast, those seen in Seclusion are grey, outlined in red, which gives them a completely different appearance, as if they were industrial-felt escapees from a Joseph Beuys installation. Ultimately, Archer ‘s paintings are a continuing and engrossing series of portraits: of the Wedderburn landscape; of her studio environment; and, as she describes it, ‘the internalisation of mySELF.’4

Andrew Gaynor, 2021

1The title is taken from an American friend of the artist from the late 1960s, who would end his letters with this phrase.

2Tiarney Miekus, ‘The Long Run #5: Suzanne Archer on responding to her Life’, Art Guide Australia (podcast), episode 35, 3 June 2021

3Suzanne Archer. Interview with the author, 22 June 2021

4Tiarney Miekus, ibid.