PETER SHARP

BIOGRAPHY

Peter Sharp has held solo exhibitions since 1989 in Sydney, Newcastle, Canberra, Melbourne and internationally in Germany. His work has been included in group exhibitions since 1987 throughout Australia and internationally in Paris, Chang Mai, Beijing and London. Sharp is a senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales School of Art and Design and has a Master of Fine Arts (1992) from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales. His work was acquired by the Kedumba Drawing Award in 2007 and the Grafton Regional Gallery's Jacaranda Drawing Award in 1996.

Peter Sharp received the Cite International des Arts Residence, Paris in 1997. A monograph Peter Sharp: Will to Form was published in 2012. Sharp has been a finalist in the Dobell Drawing Prize (2022, 2010, 09), the Hazelhurst Art of Paper Prize (2021, 19, 15, 13, 11, 07, 05, 03), the Sunshine Coast Art Prize (2019), Adelaide Perry Drawing Prize (2018, 10, 06), the Sulman Prize (2008, 98) and the Wynne Prize (2003, 96). His work is held in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Artbank, regional and tertiary collections in Australia and significant corporate collections.

ARTIST CV

DOWNLOAD HERE

WORKS

CONTACT GALLERY FOR PRICE INFORMATION

PAST EXHIBITIONS

ACCIDENTAL TOURIST: 1990 TO NOW

22 FEBRUARY TO 11 MARCH 2023

Over a period of thirty years, Peter Sharp has sought visual expression for a sense of reality shaped by natural phenomena. He has created extensive bodies of work about the veiled undertow of the ocean, the woven beauty of spiders’ webs and the play of light through trees. The hundred-year history of modernist, abstract painting has provided him with inspiration and an ongoing impetus to experimentation.

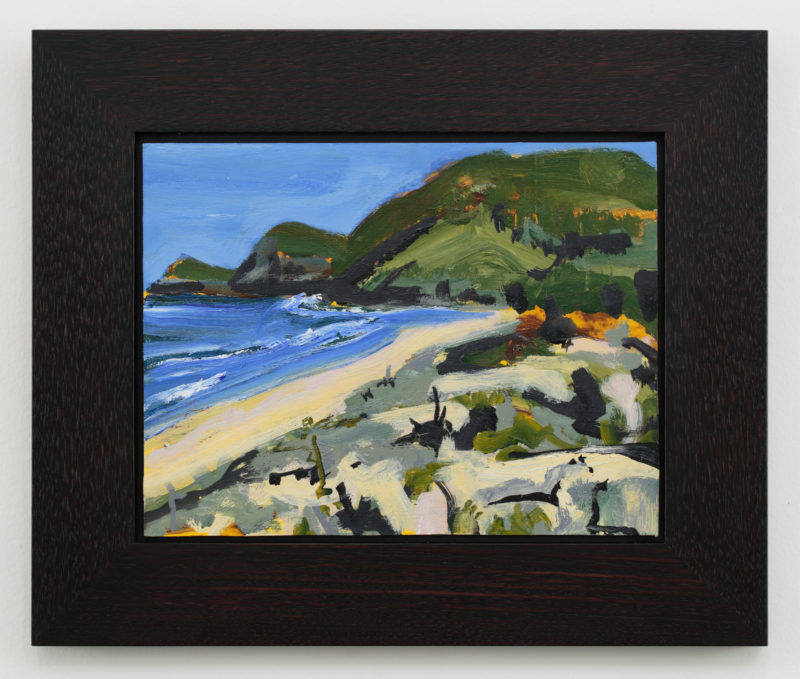

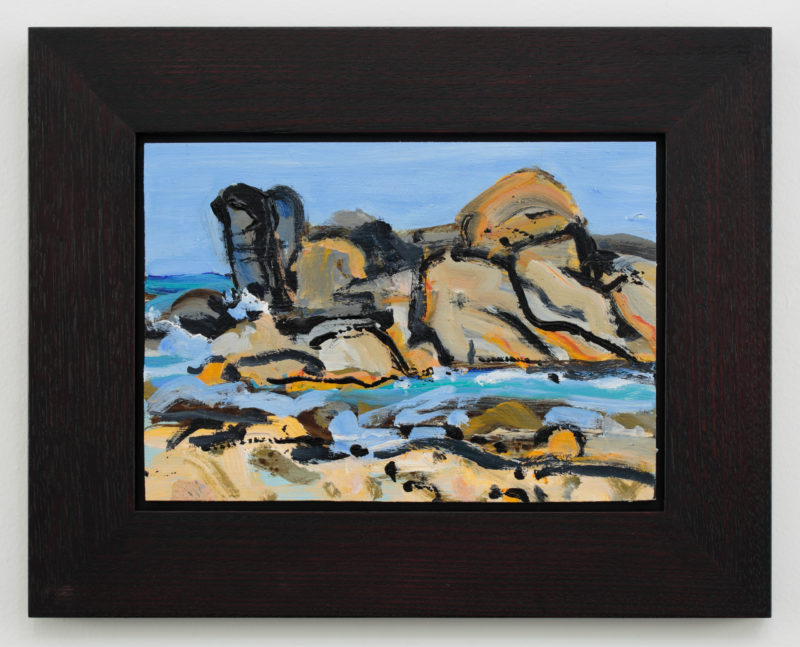

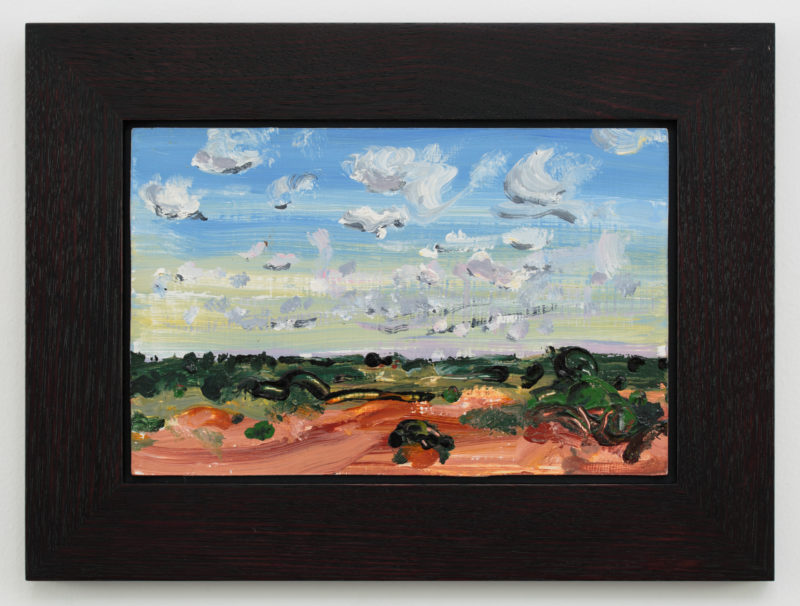

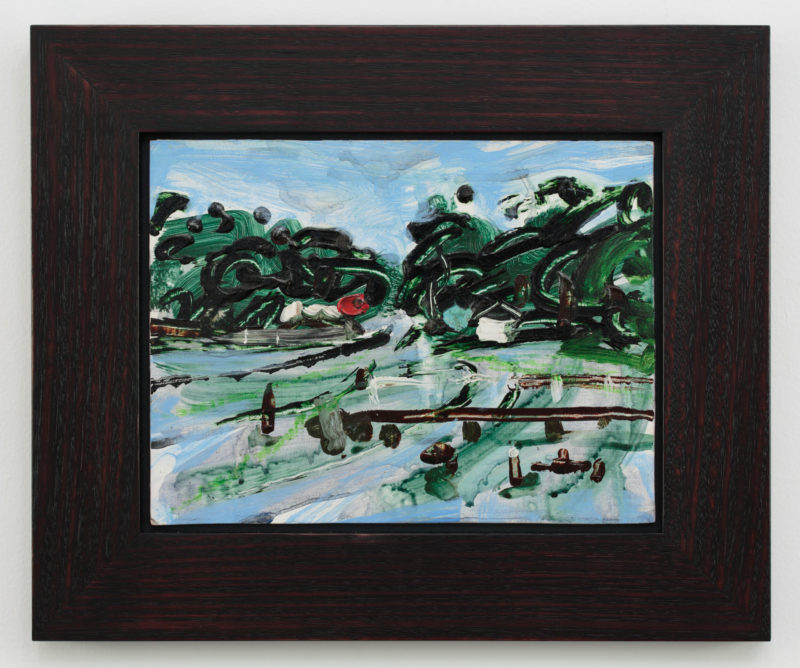

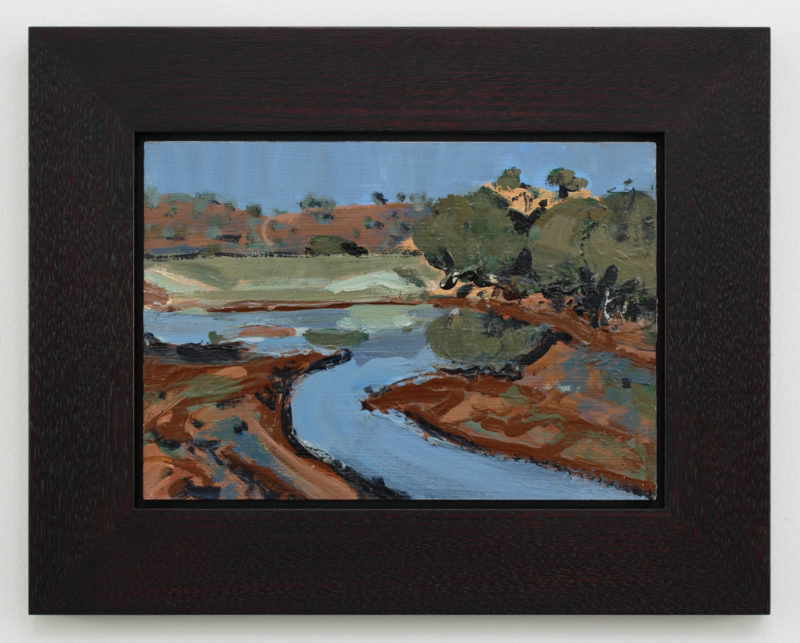

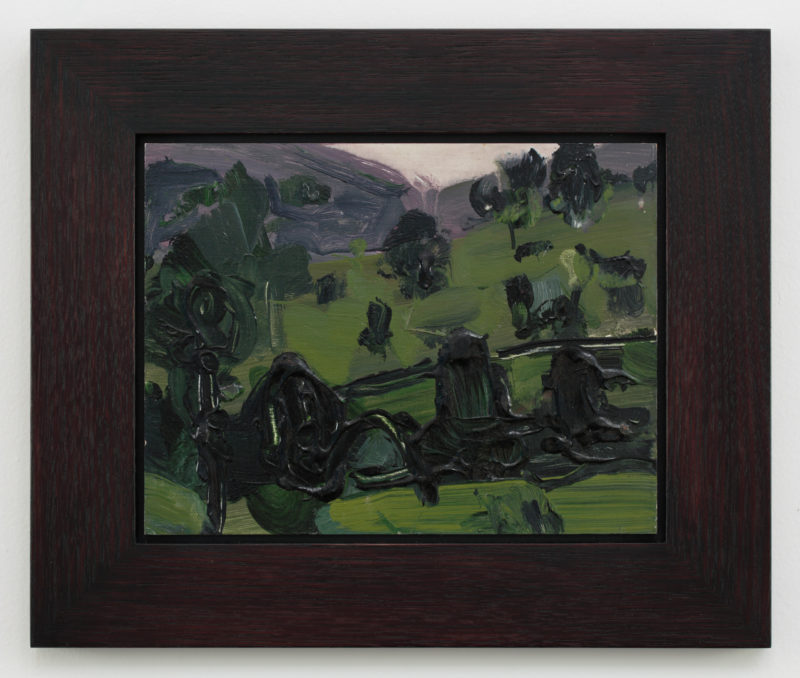

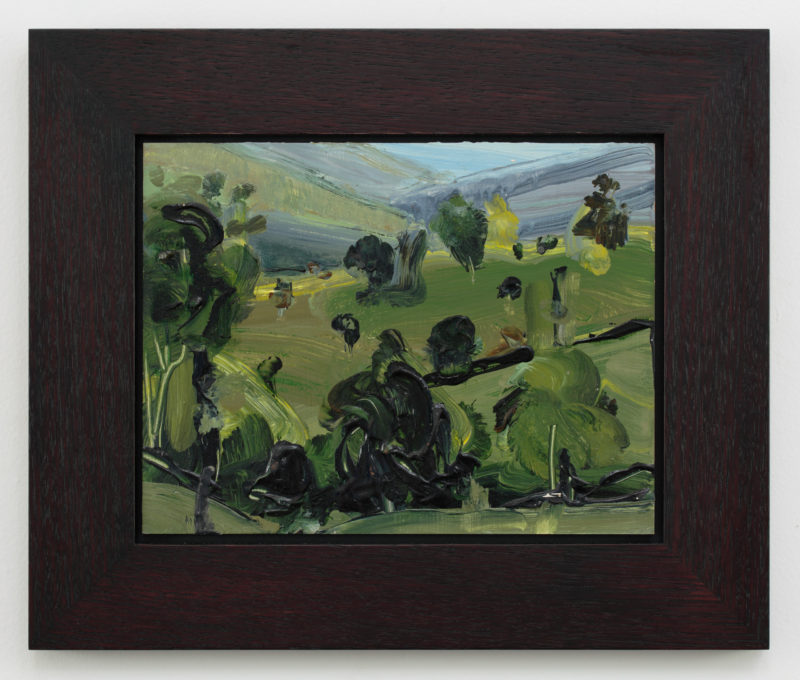

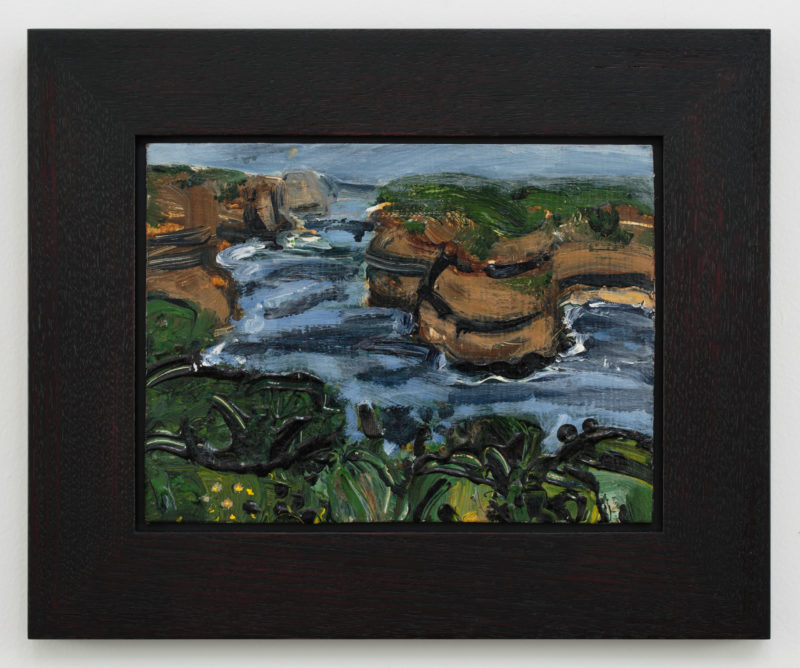

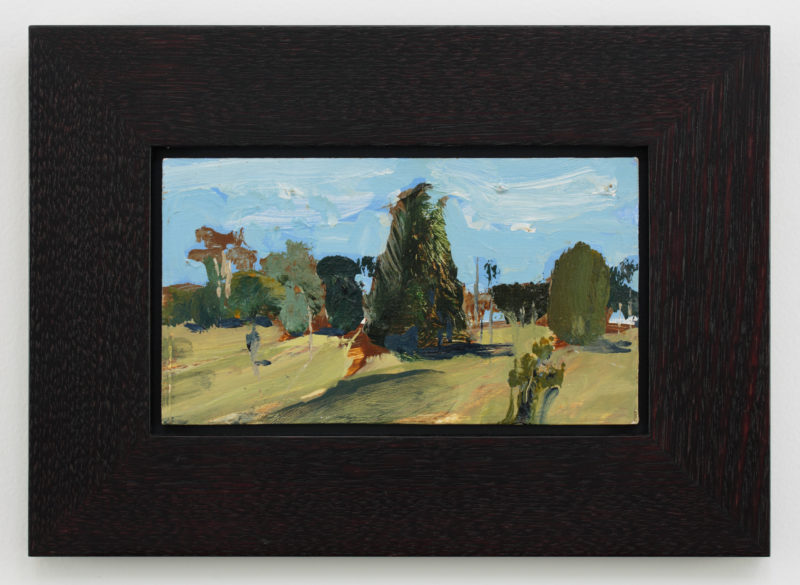

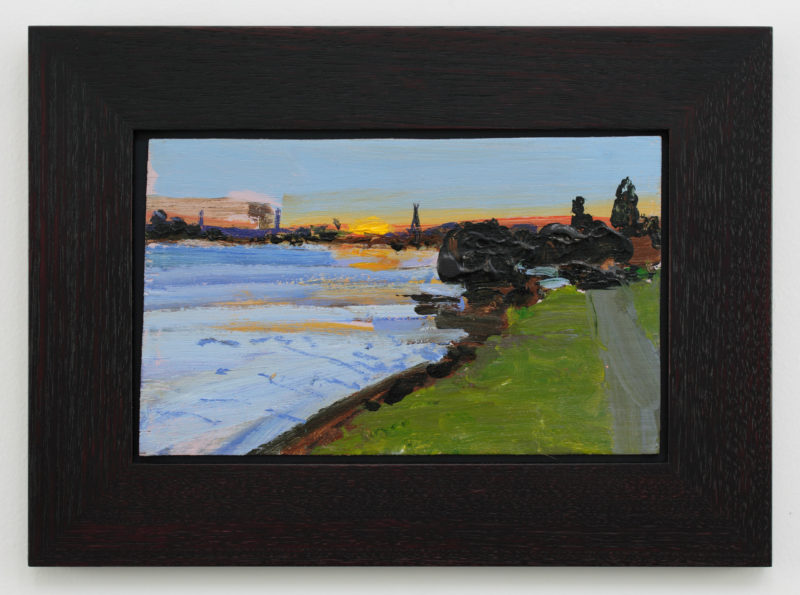

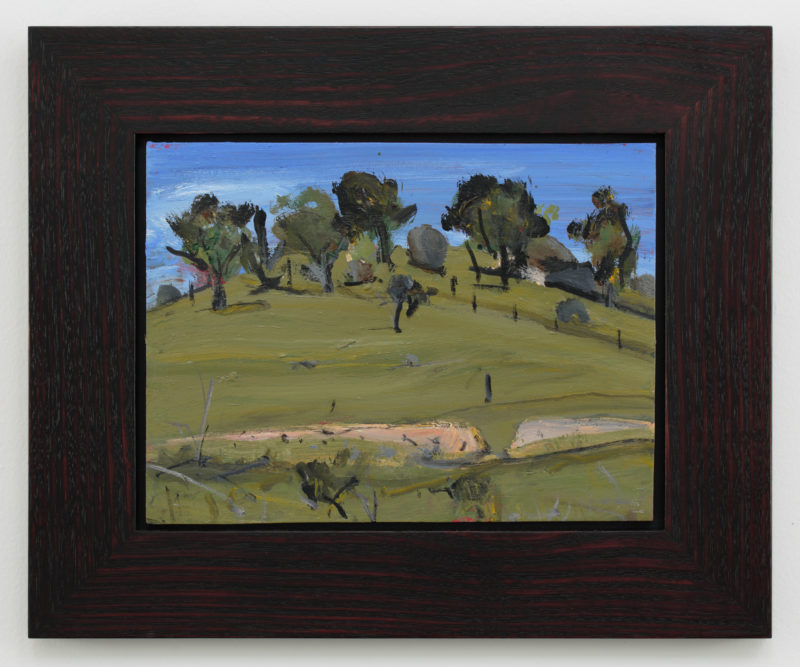

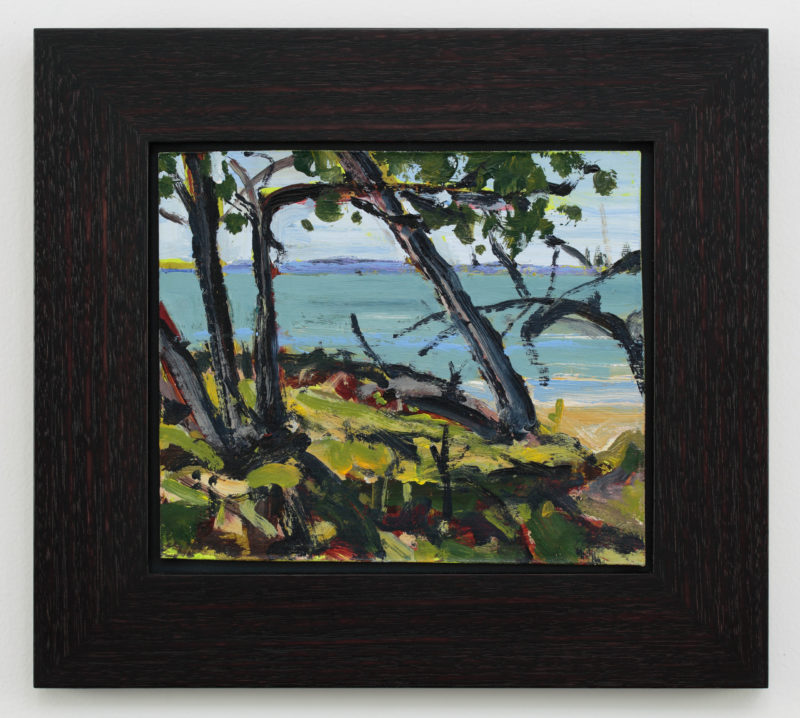

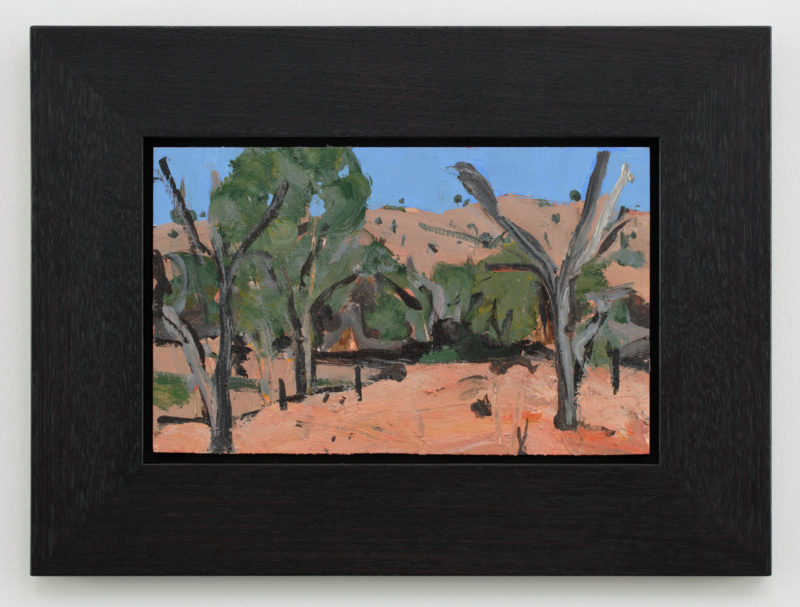

With the exception of an exhibition of plein air paintings at Sydney’s Coventry Gallery in 1994, Sharp has insisted that he is not a landscapist. He is highly aware that landscape painting in Australia is associated with the colonist’s point of view; that it has been challenged by First Nations artists who offer vital, alternative testimony on the experience of place, and that it requires re-invention by any contemporary artist who ventures back to it. Here in Accidental Tourist however, are small pictures by Sharp that land squarely within the tradition of landscape. If his name were not attached to them we probably wouldn’t be able to tell that they were his, yet they date from the same years in which he established himself through abstraction.

Their presentation asks us to reconcile the Peter Sharp we thought we knew with a very different painter. What, we might ask, does the existence of this parallel line of work mean?

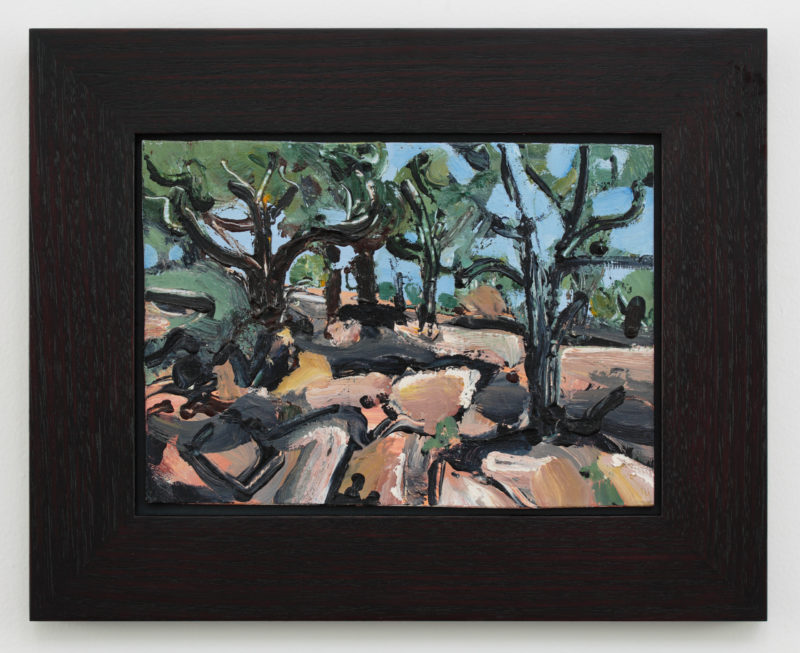

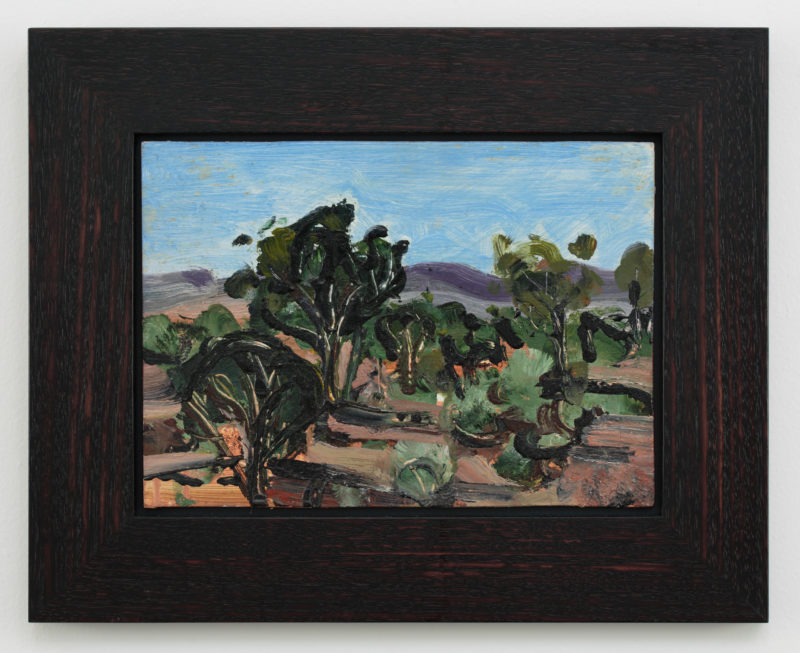

To answer this, we need to consider the circumstances of when and how it came to be painted. The occasions on which Sharp has painted outdoors at an easel have been relatively infrequent, amounting to a mere blip in time compared to the years of regular attendance at the studio. He paints en plein air when he is away from home, travelling or teaching, either for the sheer pleasure of the activity, to open himself to the challenge and stimulus of an observed subject, or to demonstrate for his students the process of making a picture. Out in the field he moves rapidly and without premeditation, asking and expecting less of painting than in the studio, but finding himself extended nevertheless by grappling with the fundamental problem of achieving a likeness.

To some observers this foray into landscape painting might be alarming, for the establishment of an artist’s reputation typically depends on maintaining an appearance of unstinting consistency. But life is not always as neat and tidy as that. It is not unusual for artists to declare a program but still crave immersion in an alternative activity, perhaps harking back to their earlier ways or heralding an idea that is yet to come to fruition. Piet Mondrian continued to make watercolour paintings of flowers into the 1920s, even though his public statements would have suggested that such an act was heresy; Philip Guston drew small caricatures of friends during his ‘abstract impressionist’ period, responding to an impulse that he was not yet prepared to acknowledge on the public stage.

What’s more, they are enjoyable to look at, in and of themselves. An early painting such as Heathcote Sunset (1993) is a small marvel, expressing an uncomplicated identification with the sun, the air and the earth’s vegetation. The sense of reverie expressed through the mobility of acrylic paint recalls, in a smaller, quieter way, the manner of Van Gogh. A pair of paintings executed in Toowoomba in 1994 and 1995 demonstrate a keen capacity to translate what was seen into a dazzling jigsaw of shapes and areas. Sharp is not a describer of fine detail. He is more interested in striking that elusive balance of elements, as simplified forms fuse into recognisable vistas. But he skilfully achieves differentiation between the textures of trees, rocks, bodies of water and the airy sky, conveying a truthful sense of the complexity of visual perception. Object and void are always in dialogue in these pictures.

The making of visual relationships that stand for an experience of being in the world, using all of the touches that painting makes available, lies at the core of Sharp’s art. This has always been true of the studio works, and it is confirmed by the plein air paintings. Over three decades, the process of abstraction that drives his studio work has become synonymous with artful arrangement; a synthesis of forms and materials that envelops the viewer in a pleasing sense of equilibrium. This is no small achievement, but the plein air paintings carry reminders of the raw talent that was evident from the start of his career and the unpremeditated approach that characterised earlier work. These qualities have remained very much alive in the outdoors, and his much-admired feeling for beauty does not prevent him from making, on occasion, more ragged images. We might not have believed that the creator of the abstractions did all of the paintings shown here.

If we wish to, we can enjoy Peter Sharp’s plein air paintings for the many delights they offer, asking nothing more. They stand as a body of work. If we want to understand the artist in his entirety, this exhibition reveals the complex, even contradictory impulses that animate his aesthetic intelligence, and reminds us of the breadth of resources he draws upon.

Joe Frost, 2021

edited from Accidental Tourist touring exhibition exhibition

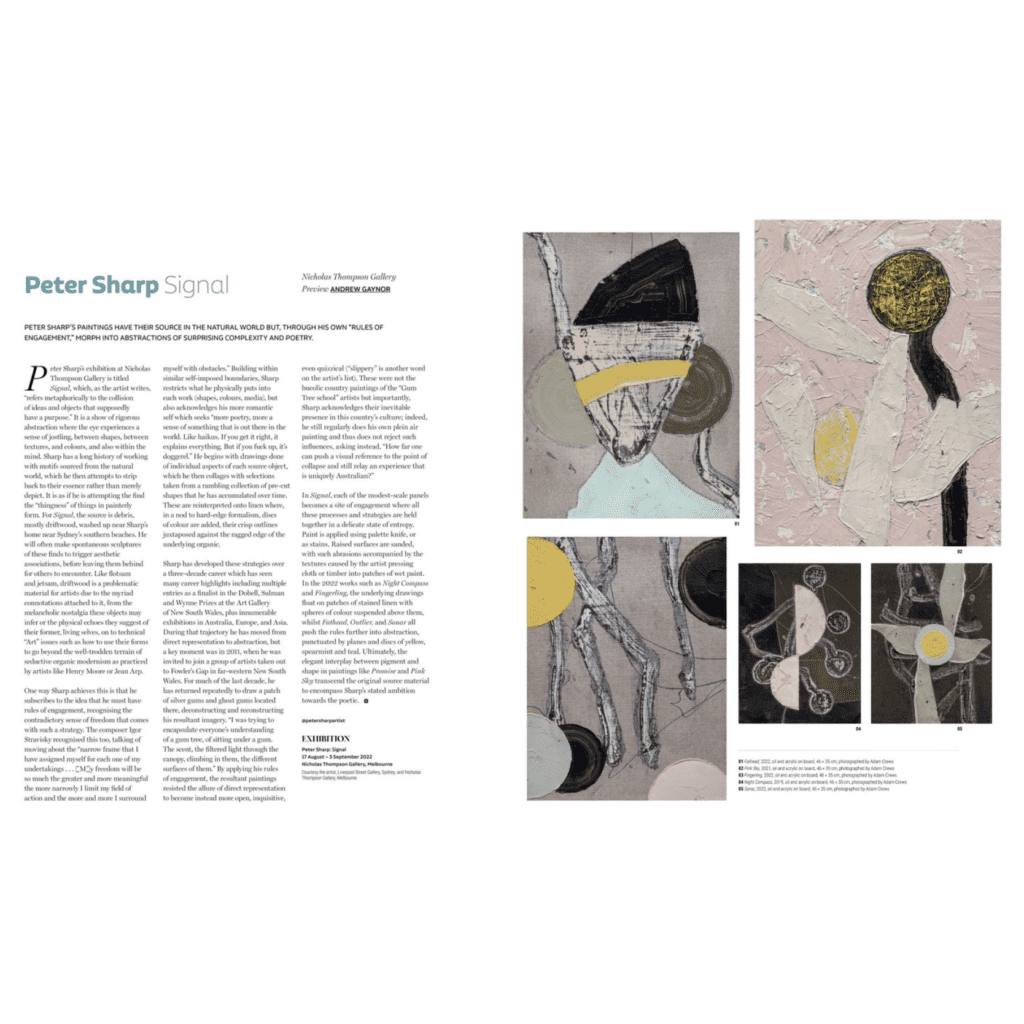

SIGNAL

17 AUGUST TO 3 SEPTEMBER 2022

EXHIBITION PRESS

Peter Sharp’s paintings have their source in the natural world but, through his own “rules of engagement,” morph into abstractions of surprising complexity and poetry. Peter Sharp’s exhibition at Nicholas Thompson Gallery is titled Signal, which, as the artist writes, “refers metaphorically to the collision of ideas and objects that supposedly have a purpose.” It is a show of rigorous abstraction where the eye experiences a sense of jostling, between shapes, between textures, and colours, and also within the mind. Sharp has a long history of working with motifs sourced from the natural world, which he then attempts to strip back to their essence rather than merely depict. It is as if he is attempting the find the “thingness” of things in painterly form. For Signal, the source is debris, mostly driftwood, washed up near Sharp’s home near Sydney’s southern beaches. He will often make spontaneous sculptures of these finds to trigger aesthetic associations, before leaving them behind for others to encounter. Like flotsam and jetsam, driftwood is a problematic material for artists due to the myriad connotations attached to it, from the melancholic nostalgia these objects may infer or the physical echoes they suggest of their former, living selves, on to technical “Art” issues such as how to use their forms to go beyond the well-trodden terrain of seductive organic modernism as practiced by artists like Henry Moore or Jean Arp.

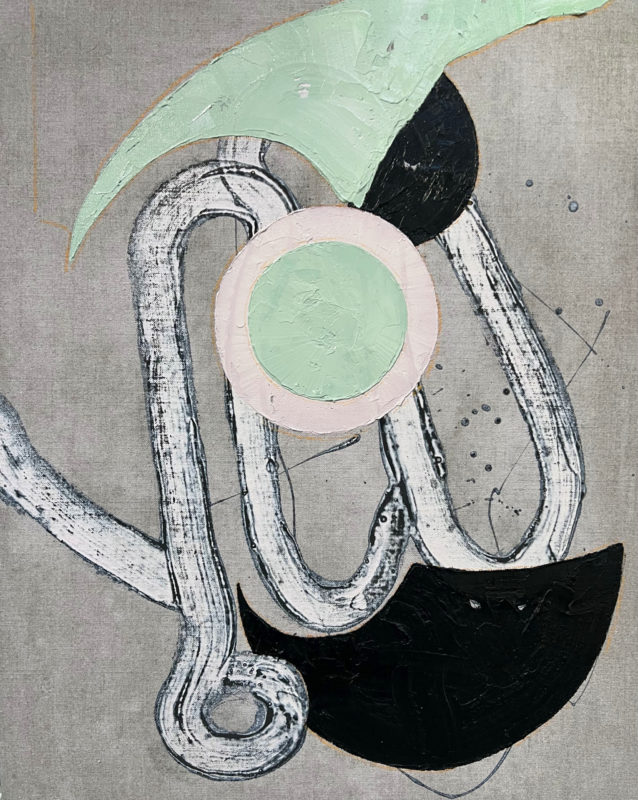

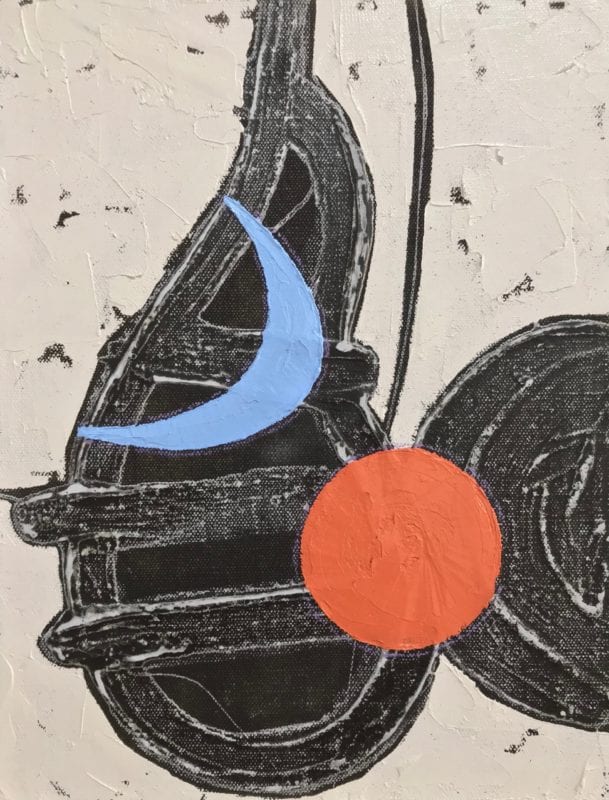

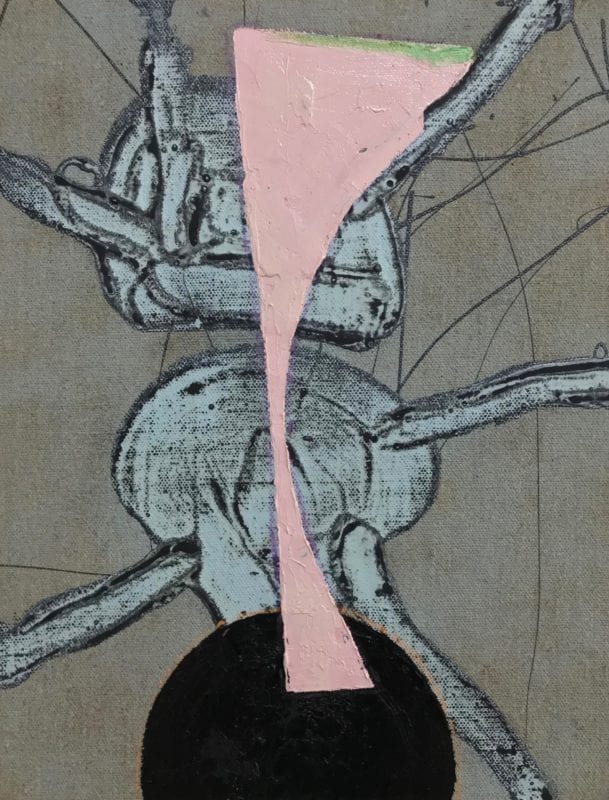

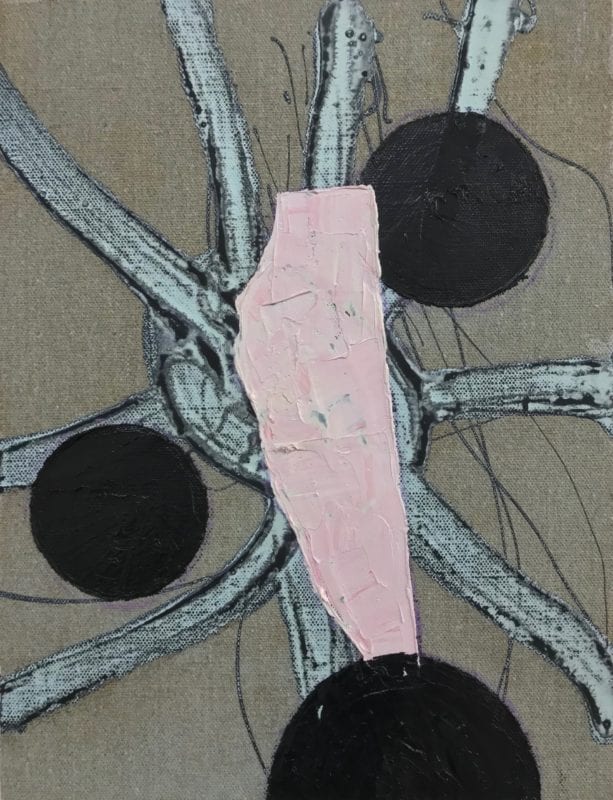

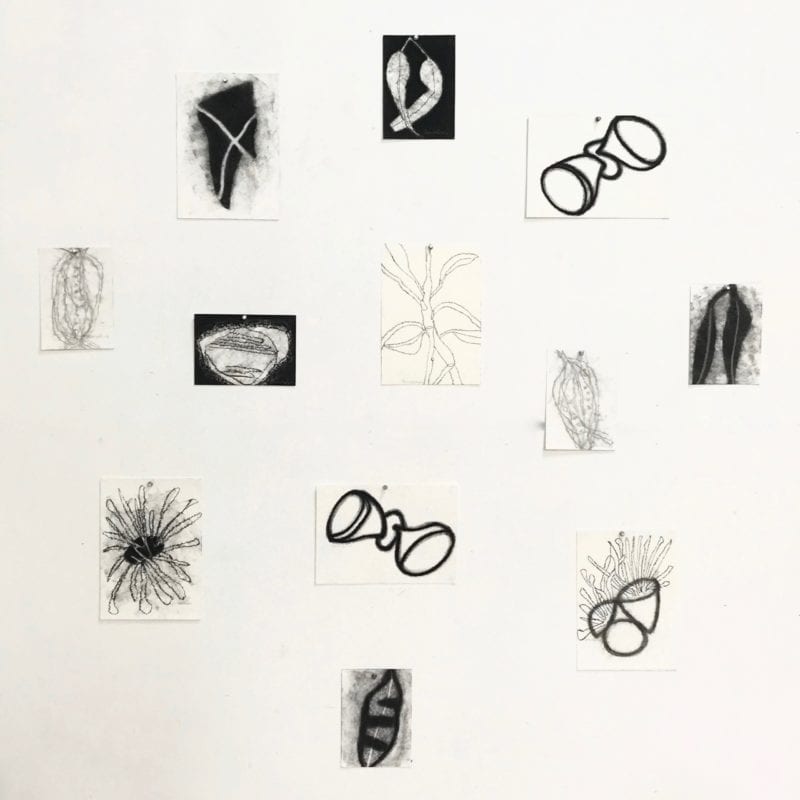

One way Sharp achieves this is that he subscribes to the idea that he must have rules of engagement, recognising the contradictory sense of freedom that comes with such a strategy. The composer Igor Stravinsky recognised this too, talking of moving about the “narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings . . . [M]y freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more and more I surround myself with obstacles.” Building within similar self-imposed boundaries, Sharp restricts what he physically puts into each work (shapes, colours, media), but also acknowledges his more romantic self which seeks “more poetry, more a sense of something that is out there in the world. Like haikus. If you get it right, it explains everything. But if you fuck up, it’s doggerel.” He begins with drawings done of individual aspects of each source object, which he then collages with selections taken from a rambling collection of pre-cut shapes that he has accumulated over time. These are reinterpreted onto linen where, in a nod to hard-edge formalism, discs of colour are added, their crisp outlines juxtaposed against the ragged edge of the underlying organic.

Sharp has developed these strategies over a three-decade career which has seen many career highlights including multiple entries as a finalist in the Dobell, Sulman and Wynne Prizes at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, plus innumerable exhibitions in Australia, Europe, and Asia. During that trajectory he has moved from direct representation to abstraction, but a key moment was in 2011, when he was invited to join a group of artists taken out to Fowler’s Gap in far-western New South Wales. For much of the last decade, he has returned repeatedly to draw a patch of silver gums and ghost gums located there, deconstructing and reconstructing his resultant imagery. “I was trying to encapsulate everyone’s understanding of a gum tree, of sitting under a gum. The scent, the filtered light through the canopy, climbing in them, the different surfaces of them.” By applying his rules of engagement, the resultant paintings resisted the allure of direct representation to become instead more open, inquisitive, even quizzical (“slippery” is another word on the artist’s list). These were not the bucolic country paintings of the “Gum Tree school” artists but importantly, Sharp acknowledges their inevitable presence in this country’s culture; indeed, he still regularly does his own plein air painting and thus does not reject such influences, asking instead, “How far one can push a visual reference to the point of collapse and still relay an experience that is uniquely Australian?”

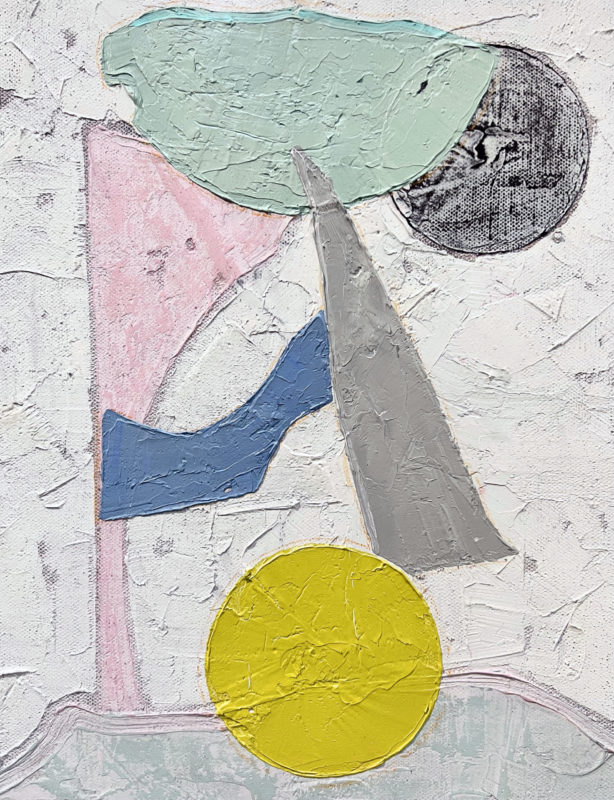

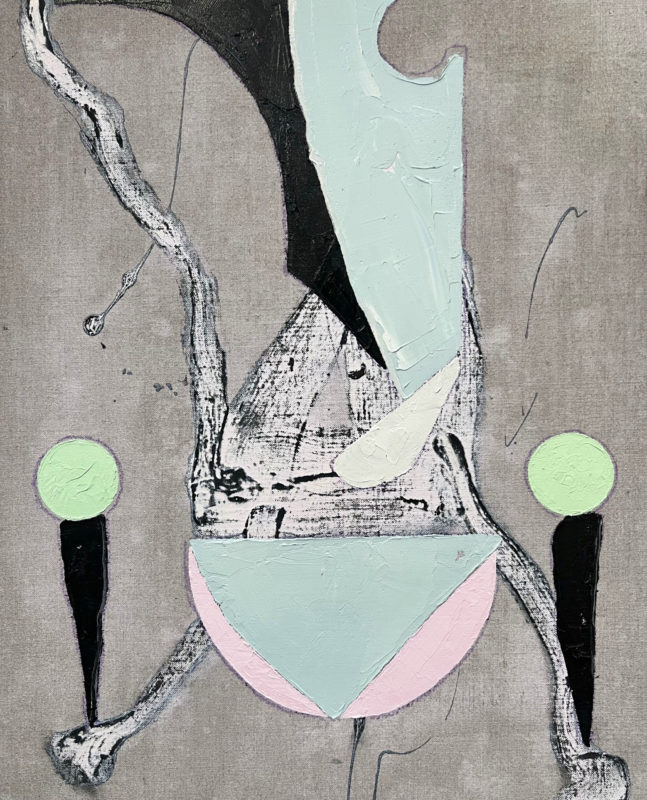

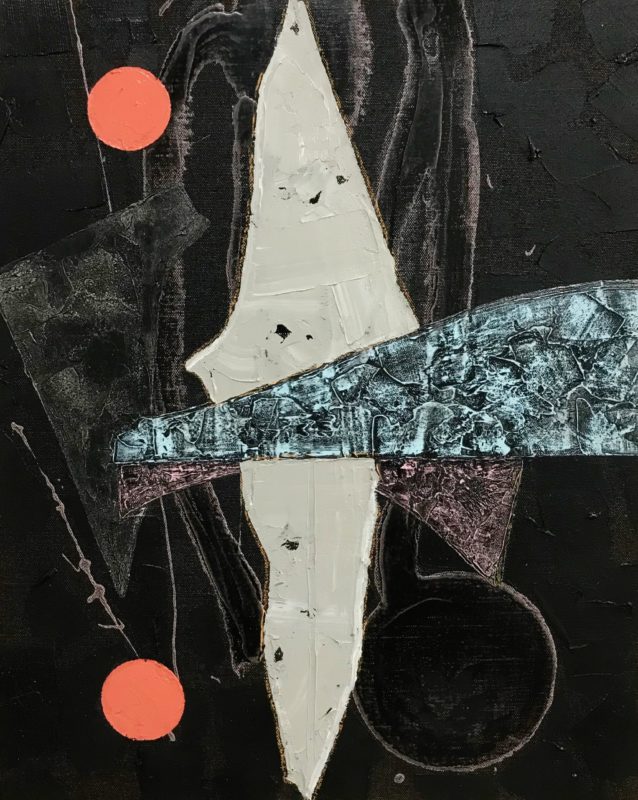

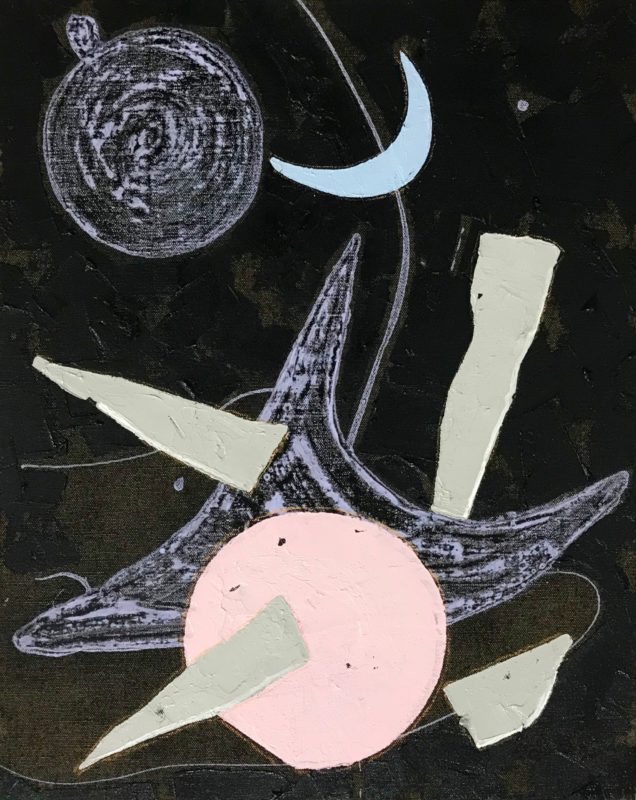

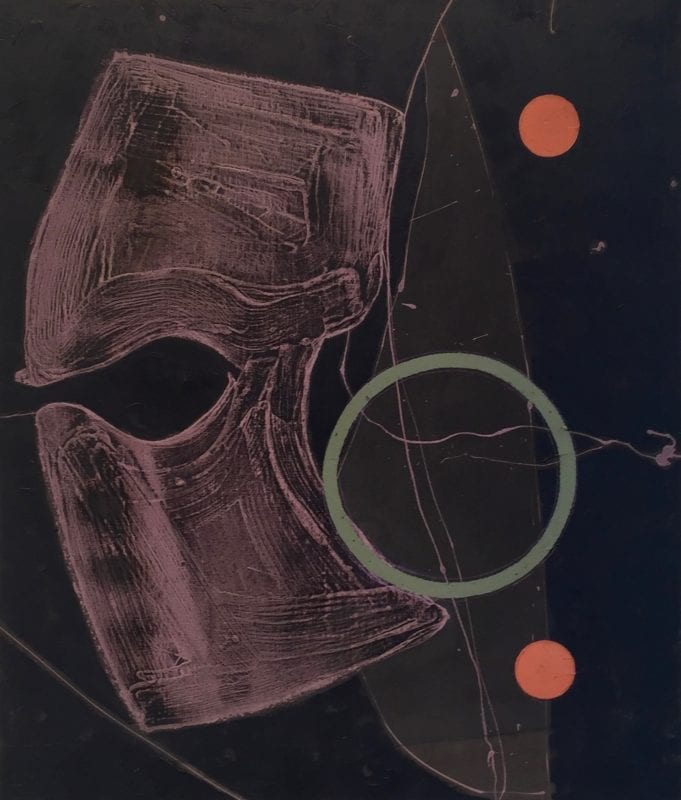

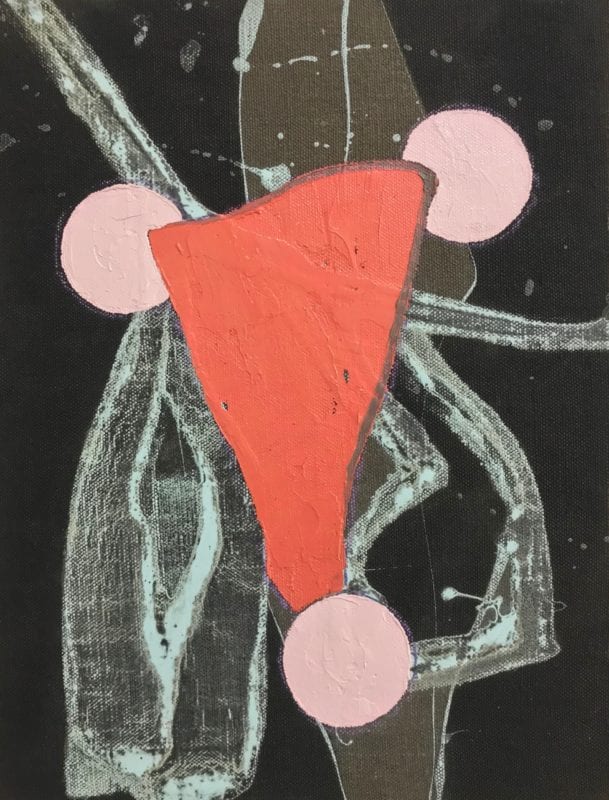

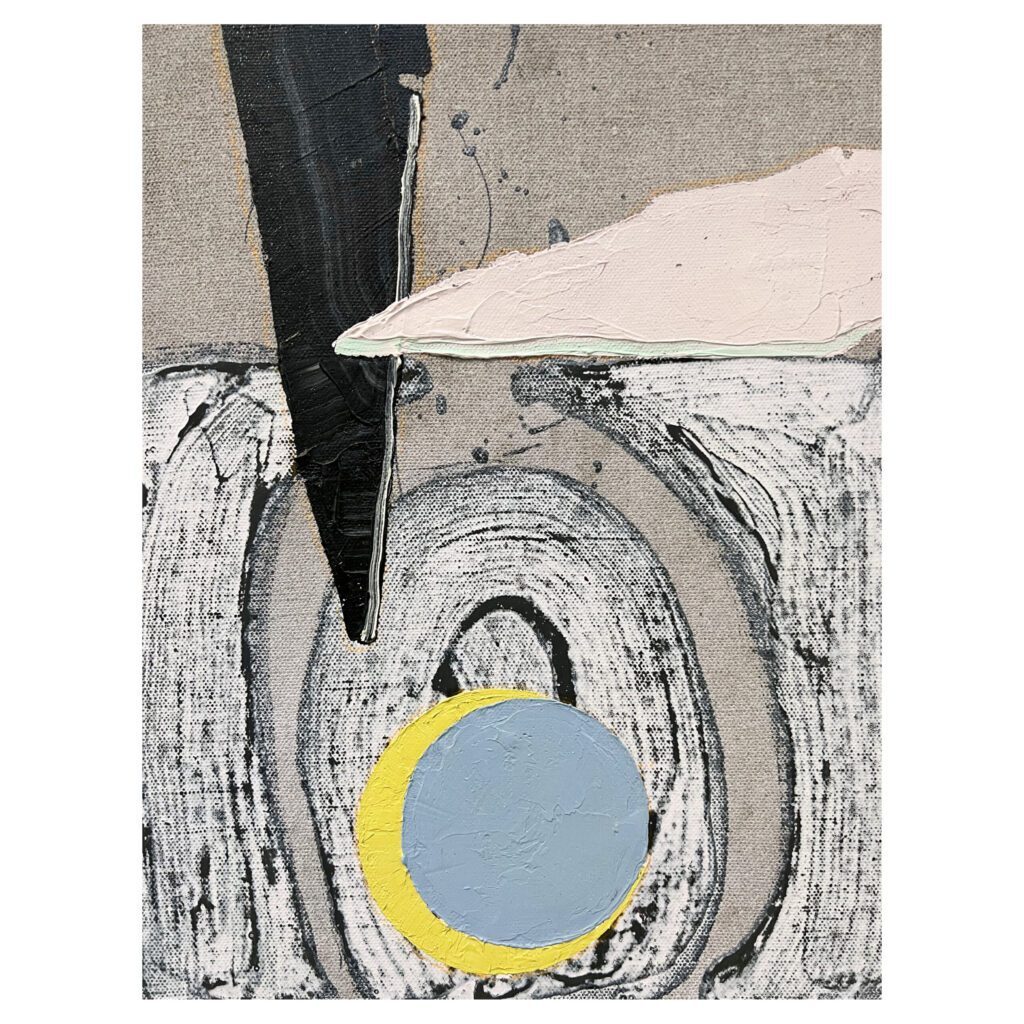

In Signal, each of the modest-scale panels becomes a site of engagement where all these processes and strategies are held together in a delicate state of entropy. Paint is applied using palette knife, or as stains. Raised surfaces are sanded, with such abrasions accompanied by the textures caused by the artist pressing cloth or timber into patches of wet paint. In the 2022 works such as Night Compass and Fingerling, the underlying drawings float on patches of stained linen with spheres of colour suspended above them, whilst Fathead and Outlier push the rules further into abstraction, punctuated by planes and discs of yellow, spearmint and teal. Ultimately, the elegant interplay between pigment and shape in paintings like Pink Sky transcend the original source material to encompass Sharp’s stated ambition towards the poetic.

Andrew Gaynor

This article was originally published in Artist Profile, Issue 59, 2022.

OPENING SPEECH

Welcome to Naarm Peter and thank you for the opportunity to speak about your work in this marvellous exhibition tonight.

It's always an honour to be asked to open another artist’s exhibition and, in particular, an out-of-town artist who we may not know so closely here in Melbourne. ….Let me tell you just a little bit about Peter. He's in his 50s, he's been practising seriously for some 30 years, he has staged over 30 solo shows and has been included in many group shows both here and overseas. In 2001 he participated in Two Thirds Sky an award winning TV documentary that saw his works compared with those of Judy Watson, Gloria Petyarre, Idris Murphy and Jenny Sages in an exploration of different visual languages that interpreted desert country.

So, Peter is a very well-established working artist. One who in my opinion deserves to be much more fulsomely known here in our town. One of the things I guess that I have in common with Peter is that he is also a teacher and for those of you that know me well, you know that a substantial part of my life was also given over to interactions with much younger artists through teaching and research.

I've been interested in my discussions with Peter that we find ourselves often speaking to the idea of what can be taught and what cannot be taught and how important it is particularly in these times of rapid image transfer to impart the worth of slow-hand mediums like painting and drawing.

I know also that Peter's past and present involves fishing, surfing, being around waterways and being in the land. He is an artist who is deeply connected to the natural environment and certainly for a large part of his practise he has adopted abstract motifs that in oblique but telling ways reference the Australian environment. Now that’s a nutshell background.

In this exhibition Signal, Peter it seems to me does indeed signal something else though… Whilst the elegant tumble of forms may connote references to his immediate external environment, I sense also a desire to explore a sense of interiority. And the colours too, whilst perhaps making reference to sky, sea, sun and so on, are without doubt also riffing off found surfaces – plasticky, acidic, invented tones are inextricably intertwined with more natural ones. I feel as though I’m looking out upon the sunshine, but from the dark vantage-point of a garage workshop table. The forms are as much bric-a-brac as they are landscape. They are as much mechanical as they are organic. It’s hard to pin down the forms. The artist has intentionally left them in a state of suspension, whereby we as viewers are perpetually on the cusp of recognising their origin, and then right at that point, the forms quietly offer up an alternative identification.

Forgive me Peter, for foregrounding the pictoriality of these paintings, I am after all bound by my own figurative impulse to find representation where perhaps ultimately none exists – but isn’t it fun to come to know work as though we were appraising it in a dream?

When I was much younger, I read Hal Foster’s Compulsive Beauty. In this seminal book, Foster reads surrealism as a dark-side art: an art given over to the uncanny.

So, I’ve been viewing therefore, a lot of art over the years from the perspective of familiar things made strange through the recall of the repressed or fragmentary remembrances.

And, yes, I guess this is something I sense very strongly in Peter’s show this time round. He has this, ….well….UNCANNY ability to bring forth forms that trigger in each of us of different associations. Whilst the luscious materiality too of the paint- its quiddity- might gently offer clues as to what we are sensing, the associations remain subjective for each viewer, and importantly Peter keeps things nice and open. You get beautifully made cues, but you must do your own delivery. And most importantly of all, Peter has this great gift of knowing just when to suspend action. Stillness abounds.

Let’s be clear, Peter is not a surrealist, but maybe…. just maybe he’s a dreamer. I’m pretty sure he is.

Congratulations Peter on a beautiful painting show and congratulations Nick Thompson too on a beautiful installation, the paintings really sing in this space.

Jon Cattapan, 2022

GOING SOMEWHERE ELSE

21 OCTOBER TO 8 NOVEMBER 2020

‘Expectation prevents discovery’.[1]

In Bruce Springsteen’s 2019 song Hitch Hikin’, the singer describes a solitary figure, thumbing his way along from one place to another, happy to be on the open road, heading somewhere else. There is no sense of urgency, and destination is eschewed in favour of discovery; a promise of time alone with your thoughts and with yourself. In artist Peter Sharp’s most recent body of work there is that familiar/unfamiliar feeling that comes from taking a detour away from a known path and travelling a byway instead.

The works in Going Somewhere Else propose a different route. While the paintings contain remnants of his 10-year engagement with the ubiquitous Australian eucalypt, the artist is moving on, curious to see where the road might take him, happy not to answer questions but to pose them instead. Though he still employs the same methods of observation and deconstruction he has in the past (the artist is known for his idiosyncratic charcoal drawings of the natural world), these new paintings emphasise the unexpected encounters that occur through his reconstructive processes.

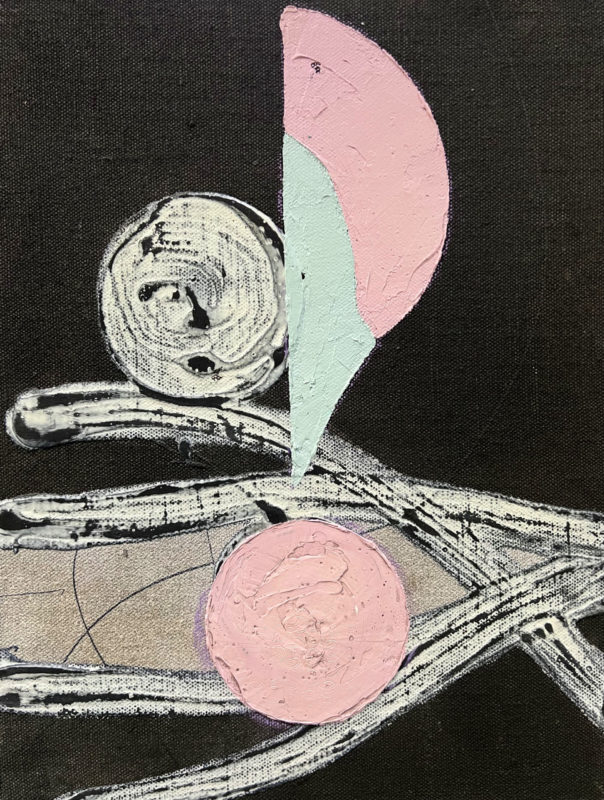

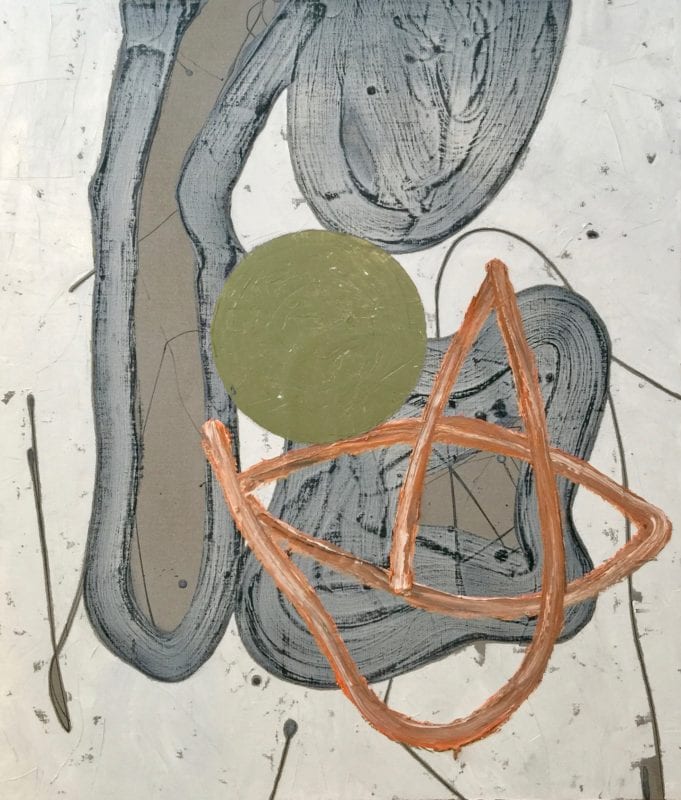

In the new works, Sharp has abandoned his concern for mnemonic referents through which an audience might link forms and shapes back to their eucalypt source. Instead he is more concerned with the materiality of the paint and the hard, fuzzy, spikey, flat textures and raw ‘object-ness’ of the natural world that underscores his practice. This is evident in Sharp’s approach to his paintings where inky voids contrast gum grey arabesques of line that reference the charcoal drawings but refuse mimetic representation; teasingly buried under areas of flat colour that no longer sample the eucalypt directly, but obliquely reference their source. Salmon hued orange fragments stretch across bark-like textures in dark greys and weathered blues, while minty green, hard-edged arcs push against organic forms creating delicious tensions that seem familiar but are not. Sharp’s customary circles, here in musk stick pink, punctuate the compositions like signposts on a road and generate a gentle rhythm linking one work to the next.

Long admired by Sharp, the late American abstractionist Thomas Nozkowski had a habit of walking to work via a different route each time. He did this because he ‘loved to take walks [and] always wanted to find something new. He had a kind of voracious curiosity’.[2] Interested in what he might find along the way, this anecdote provides a perfect analogy for the approach that Sharp has taken with this new body of work. Like Nozkowski, Sharp is always alert to the possibilities that lie within the rectangular constraints of his linen supports, resisting the familiar in favour of chance encounter.

Michelle Cawthorn, July 2020

[1] Suri Hustvedt, 2005, Mysteries of the Rectangle, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, p xix

[2] John Yau in conversation with Hrag Vartanian, podcast EP68, Hyperallergic, 15 May 2020 <https://hyperallergic.com/564592/art-critic-john-yau/> accessed 20 July 2020

HOW TO PAINT TREES

4 TO 22 JULY 2018

“Kiss me……..I want you to kiss me like a stranger once again”

Peter Sharp - How to paint trees

Beyond my window is a sinuous Jackwood that is gently brushing the glass pane. I have known this tree for 13 years and yet, on days like today when the rain lightly falls, and the pale green lichen is luminous in the grey light, I wonder again at this beauty I am so familiar with. For me, that moment of wonder is enough, but for artist Peter Sharp, it is a provocation. The more familiar that Sharp becomes with a subject, the more determined he is to interrogate it, to know it beyond the superficial, to re-cognise it anew. But how do you make the familiar pulse with the thrill of first discovery? How do you convey that seduction of colour and shape, the smells and sounds of first encounter?

This is a challenge that Sharp relishes in his practice. For the body of work presented here, the subject of his interrogation are the trees of Fowlers Gap, an arid zone at the edge of the Strzelecki desert in far western New South Wales, a site he has visited many times over the years. While some would be tempted to render this landscape in its entirety, Sharp’s is an intimate approach, concerned with the minutia, foregoing the whole for the sum of its parts.

His investigation begins with drawing; swiftly noting shape and form with a gestural ease that belies the rigorous process of observation and recording that informs each one. The drawing is active and exploratory; purposely disrupting the connection between eye and paper through a process of rubbing that creates a friction; generating a tension in the drawings that is conveyed both literally and metaphorically.

But this is only part of a process that constitutes Sharp’s re-cognising of his subject. For Sharp the drawings are like specimens collected in the field and they hold the key to his way into the paintings. From them he extracts forms which he then transposes onto canvas with acrylic paint in loose and languid lines. The marks are made quickly, as they are with the drawings, but the method of application mediates his control, the drips and drops of the paint falling where they may through this process of transference. But for Sharp, this is not enough.

There’s line from a Tom Waits song that goes like this;

“Kiss me

I want you to kiss me

Like a stranger once again”[i]

Waits is talking about his desire to feel anew the frisson of first touch attached to something long loved. This is analogous to Sharp’s relationship with the subject of these works. In his desire to portray his experience of a landscape he has known for more than half his life he seeks to reimagine those first encounters. It is a going to it rather than an it coming to you; not passive but active.

For Sharp, the act painting itself is a provocation, a dynamic thing. He does not underestimate the viewer nor does make apology for the fact that the viewer must work to make connections between the forms, textures and colours in his work. This equates to a transference of his experience to the viewer, that sense of discovery that Sharp himself experiences each time he steps out into the field.

Michelle Cawthorn, June 2018

[i] Bad As Me 2011, ‘Kiss Me’, Tom Waits and ANTI Records, http://www.tomwaits.com/songs/song/369/Kiss_Me/

.

NEWS

PETER SHARP IN ABC ONLINE ‘HOW BROKEN HILL’S UNIQUE LIGHT HAS DRAWN GENERATIONS OF ARTISTS TO THE NSW FAR WEST’ BY COQUOHALLA CONNOR

How Broken Hill’s unique light has drawn generations of artists to the NSW far west ABC Broken Hill / By Coquohalla Connor Peter Sharp, a senior lecturer in painting and drawing at the University of New South Wales, made the same trip in the 1990s. “I was drawn out there because it was a romantic…

PETER SHARP FINALIST IN 2023 MOSMAN ART PRIZE

Peter Sharp is exhibited as a finalist in the 2023 Mosman Art Prize The Mosman Art Prize is the longest running and most prestigious municipal art prize in Australia. Winning entries form the basis of the Mosman Art Collection, a valuable and historic collection that surveys Australian painting since 1947. Exhibition current to the 29th…

PETER SHARP FINALIST IN THE DOBELL DRAWING PRIZE 22

Peter Sharp is a finalist in The Dobell Drawing Prize 22 . The Dobell Drawing Prize is the leading drawing exhibition in Australia. Presented in partnership with the Sir William Dobell Art Foundation (SWDAF), the biennial prize explores the enduring importance of drawing within contemporary art practice. . The exhibition is current at the National…

PETER SHARP FEATURED WITH MICHELLE CAWTHORN IN ART COLLECTOR’S ‘YOU ME & COVID-19 SERIES’

YOU ME & COVID-19: MICHELLE CAWTHORN AND PETER SHARP The You, Me & COVID-19 series sees the region’s artists interviewed by the partners they’re sharing #iso with. Watch artists and partners Michelle Cawthorn and Peter Sharp in conversation from their home in the Sutherland Shire. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=pSBbL1ioeUw&feature=emb_logo