KYLIE BANYARD

BIOGRAPHY

Kylie Banyard is a multidisciplinary artist and educator. Her artistic practice is grounded in painting and intersects with photography, video, sculpture and immersive architectural spaces. Banyard was included in The National 2019: New Australian Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and recently completed a VR Studio with Tactical Spacelab (funded by the Australia Council and Arts NSW). She has been included in significant group exhibitions including Art from Down Under: Australia to New Zealand, Turchin Center for the Visual Arts, North Carolina (2018); Another Green World, The Western Plains Cultural Centre (2017); The Mnemonic Mirror, Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane, and UTS Gallery, Sydney (2016-2017).

Banyard has received competitive funding from Arts NSW and the National Association for the Visual Arts, as well as postgraduate research grants including the Australian Postgraduate Award from the University of NSW and the COFA, UNSW Travel Grant. She has been the recipient of several competitive artist’s residencies, such as the Cité International des Arts Paris, France and the Firstdraft Emerging Studio Residency Program, Sydney.

Banyard has been a finalist in the Arthur Guy Memorial Painting Prize, the Ravenswood Australian Women’s Art Prize and was awarded the National Tertiary Art Prize and The Basil and Muriel Art’s Scholarship, Art Gallery of NSW. She has a PhD in Fine Arts from the University of NSW and is a Lecturer of Visual Art at La Trobe University. Banyard’s work is held in numerous public and private collections including Artbank, Australia.

ARTIST CV

DOWNLOAD PDF

WORKS

CONTACT GALLERY FOR PRICE INFORMATION

PAST EXHIBITIONS

BECOMING SESSILE

2 TO 19 NOVEMBER 2022

How can we speak of the vegetal world? Is not one of its teachings to show without saying, or to say without words?[1]

Luce Irigaray

Becoming Sessile opens new pathways in Kylie Banyard’s approach to making paintings. For this body of work, she has turned away from the historical archive to make a break with her longstanding interest in looking to the past. Still pre-occupied with the criticality of the utopian imagination, these new works respond to a daily ritual shared with her six-year-old son. Affectionally known as touching and performed on walks together, the two document their sensory and affective encounters touching and talking to plants. As Donna Haraway would say, “we need to find ways of staying with the trouble, to rebuild quiet places, shift our daydreams and our fantasies towards finding earthly ways of being present and connecting with our damaged earth”[2]. Together they photograph each other’s careful touch, wilfully suspending the moment of contact while discussing the way different plants feel and smell. Their ritualised encounters with vegetal beings seek to acknowledge the plant’s peculiar subjectivity and recognise their strange alterity and unsuspecting agency. This investigation is then extended in the painting studio where Banyard spends time tending to the details that emerge within her photographic source. To be sessile, like a plant, is to be anchored in place. Plants choose to embed themselves in their milieu, and these paintings and the collaborative research that led to their making, raises questions about what careful time spent encountering and contemplating the lives of these enigmatic more-than-human keepers-of-place might teach us about other ways of being in and of the world.[3]

[1] Irigaray, Luce and Marder, Michael. Through Vegetal Being, ‘Prologue’, New York, 2016.

[2] Haraway, Donna. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, 2016, p. 18.

[3] Clark, Martin. The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism and the Cosmic Tree, ‘On Being Sessile’, Camden Art Centre, 2021, p. 183.

TOUCHING ARCHIVES OF SUNLIGHT

Immersion, entanglement, visual hapticity, ciliated sense, the synesthetic force of perceiving-feeling, contact, affective ecology, involution, sensory attunement, arousal, response, interspecies signalling, affectively charged multisensory dance, and remembering.[1]

So reads Material Feminist Karen Barad’s list of “sensuous practices and figurations at play in feminist science studies”. Following Donna Harraway, Barad and others are forging new materialist topographies based on embodied perception and entangled positionality, united by a commitment to helping make “a more just world”.[2] Artist Kylie Banyard’s new body of work, Becoming Sessile, engages with the sensuosity of vegetal life towards this same pursuit, attune to the alterity of plants while speculating on their subjectivities.

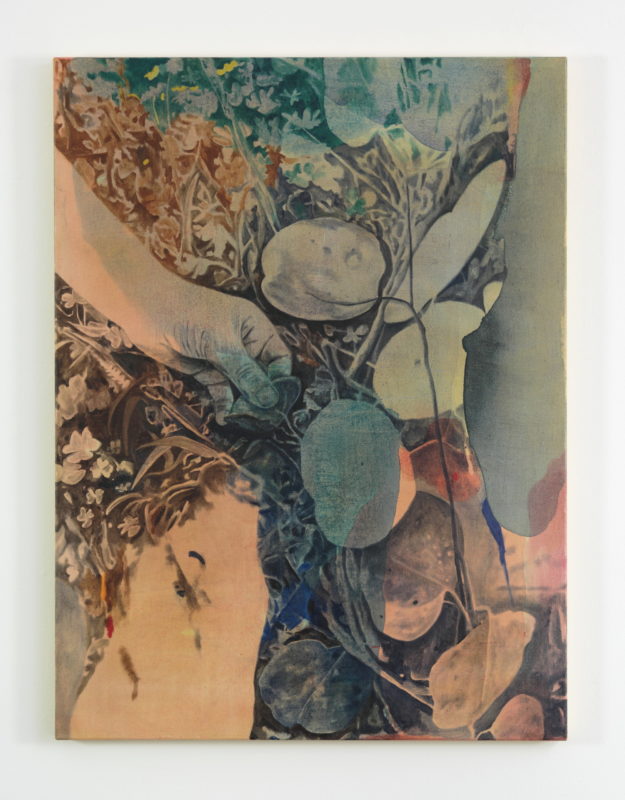

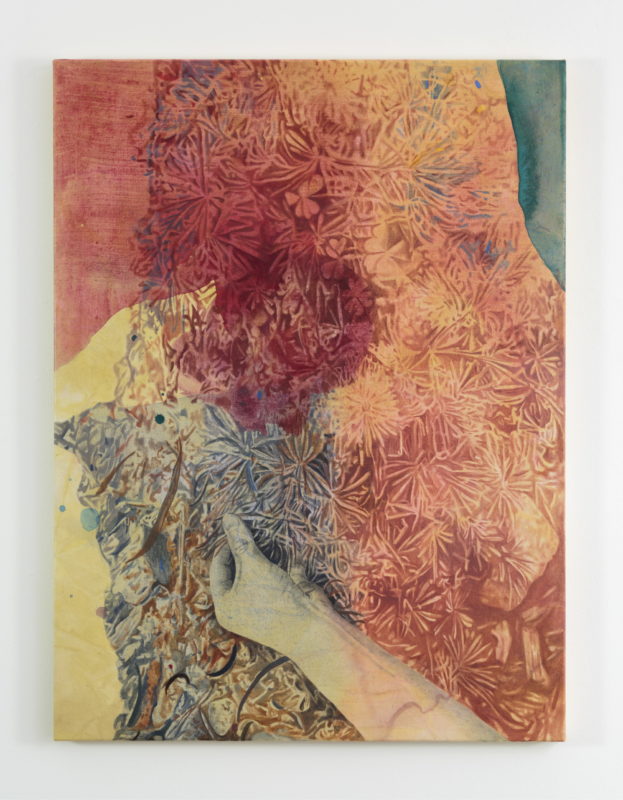

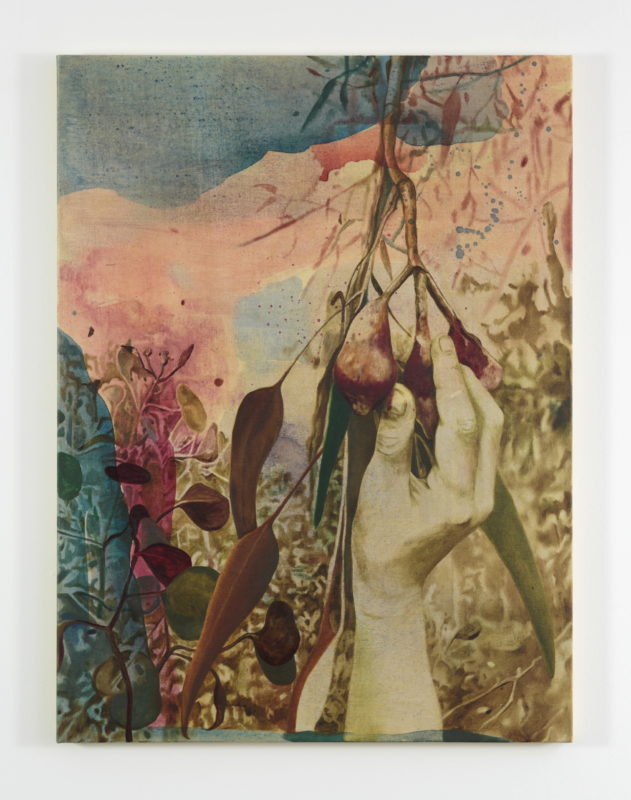

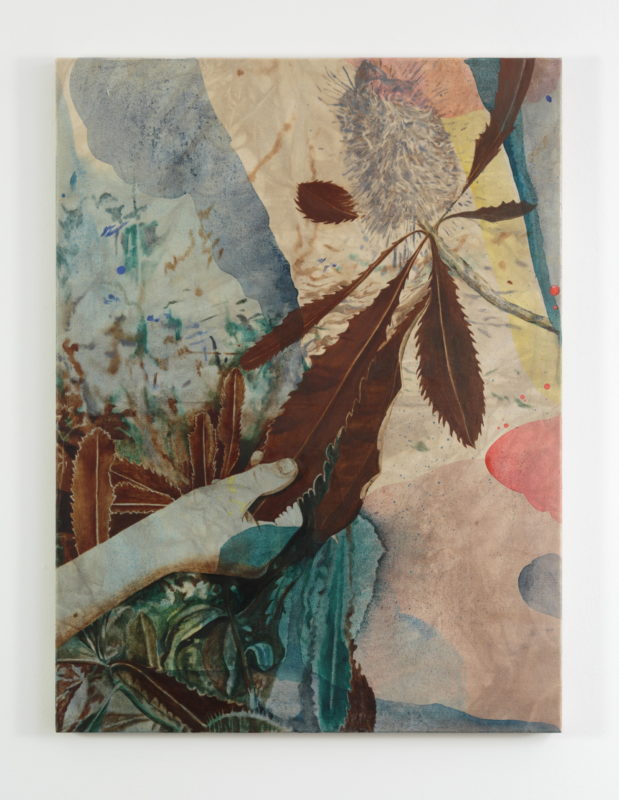

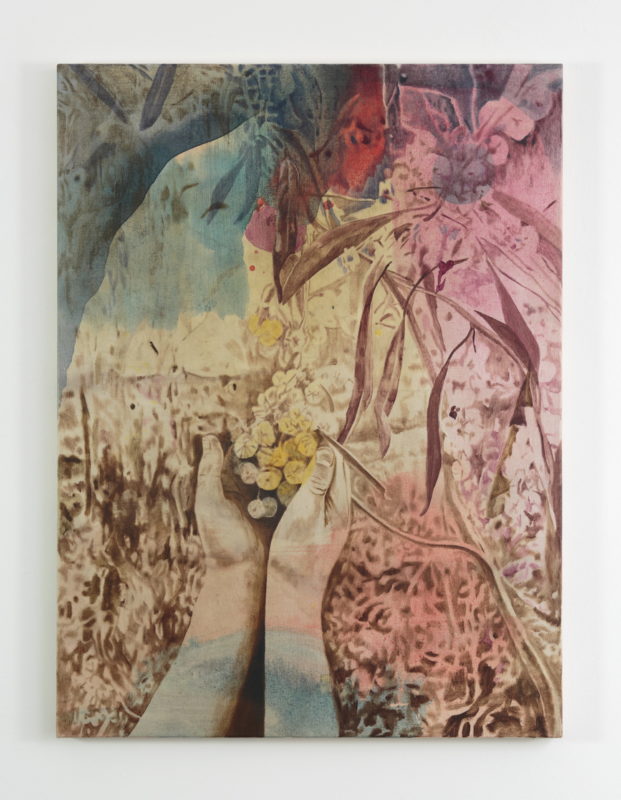

Across a series of paintings small hands hold, touch, caress the leaves and flowers of native Australian plants. Neither picked nor plucked, the touch is nevertheless precise; thumb and forefinger enclose around a stem, press against a leaf, cradle a gumnut. Stalks heavy with wattle flowers rest in open palms. This tender, deliberate touch is enacted by the artist’s young son, on daily walks through bush and suburban streets; what originated as an incidental moment became an intentional ritual between mother and son. These moments are tenderly photographed by Banyard and inform the basis of her new body of work and a new direction in her practice.

The relationship between painting and photography has long been of interest to Banyard, whose previous works have reconstructed historical photographic archives and investigated obsolete cameraless photographic techniques such as the cyanotype. Earlier bodies of work have reanimated the activities of the radical Black Mountain College (1933–56), foregrounding the contribution of the school’s female participants. Driving this impulse to engage in historic materials is a desire and belief in alternative possibilities of living and working. In Banyard’s practice, pedagogy of imagination and utopian thinking is key to the speculation and potential creation of a more just and ethical world. This new body of work maintains this commitment, whilst turning from the historic photographic archive to what curator Martin Clark termed “archives of sunlight”: the vegetal world.[3]

In Becoming Sessile visual hapticity — the visual perception of touch — is threaded through each work. From the intermingling of pigments and fibres on the surface of the canvas, to the transferal of matter, to the inter-species encounters between plant and person. For these paintings, the process of creation begins with the assembly of natural pigments and plant matter which are then used to dye the canvas. After this has dried and fixed, the canvas is again stained with watery swirls of colour, reminiscent of the fluid shapes and "soak stains” of Helen Frankenthaler’s large-format floor paintings. Then begins the methodical transferal of the photographic image onto the canvas using oil paints.

Becoming Sessile presents eight variations of the ritualised “touching” encounter between mother, son and plant. The word “touching” is echoed across the title of eight paintings, followed by the awkward anglicised and anthropomorphic names for the native plants: “Dollar Gum”, “Silver Princess”, “Drumstick”. These common plant names, with their capitalist and feudal associations, are an attempt to embed plants within colonial Western logic, to make them familiar rather than revel in their unknowability. However, the reverence of touch between child and plant depicted in the paintings returns the plants to their true state of otherness, respecting their “strange alterity” and the “uniqueness of their existence.”[4]

In biology, the state of sessility refers to sitting or resting on the surface. More broadly, it is the state of being fixed or immobile, such is the case with vegetal matter. Clark suggests that sessility necessitates a level of adaptation to survive. Whereas animals have the ability to avoid danger — through speed, motion — the sessile plant must adapt in order to face it. Plants therefore operate from a position of embeddedness. “They hold a deep, slow ancient knowledge of what it is to be in the world, and what it is to make a world”.[5] What can we learn from remaining in one place?

Banyard and I live a few minutes’ walk from each other, on Djaara. Most weekends, our sons play together, and we delight in their made-up games, full of imaginative characters, magic, karate moves and alchemic potions. Their brews are improvised from garden plant matter, with the odd household product thrown-in, carefully assembled and left to stew in jars. In Becoming Sessile, a more distilled version of this game is on view, created by the artist’s six-year-old son in an act of reciprocal collaboration. Bark and leaves are soaked until the colours run, the plant matter is drained out and only the colour and perfume remain. Displayed in the gallery in glass jars, atop an improvised platform of found bricks, Bubble Fume is a shrine to play and imagination, qualities sorely needed in the pursuit of a more just world.

When I visited Kylie at her studio, our region, indeed much of the east coast of so-called Australia, was experiencing severe weather warnings with most of the state on flood watch. The local creek that we regularly walk alongside swelled with rainwater and swallowed its banks. Walking through this watery landscape, I was reminded of the surface of Banyard’s canvases, they depict a sense of immersion, of seepage and swirling of colours, the feeling of everything washing together, background and foreground blending until there is only one surface. In the dry warmth of the studio, Banyard describes her use of oil paint as akin to using watercolours; in the instance of these paintings, there is little to no use of white paint. We talk about a lightness of touch, so the paintings are “just enough”. It is this restraint that allows the viscosity of the oils to give way to the natural and synthetic dyes underneath, drawing the dyed background of the canvases into the imagery.

“Plants are capable”, advises Philosopher Michael Marder, “of accessing, influencing, and being influenced by a world that does not overlap the human Lebenswelt but that corresponds to the vegetal modes of dwelling on and in the earth”.[6] Vegetal thinking, as proposed by Marder, reminds us that human-animals are not the fulcrum of our world. While the depth of plant knowledge is still being determined, for Banyard, their networked and non-hierarchical thinking, their sessility, offers contemplative possibilities for other ways of being in the world. Becoming Sessile operates within this affective ecology, with respect for the agency and unknowability of pants as speculative models for more gentle ways of being.

[1] Karen Barad, On Touching – The Inhuman That Therefore I Am (v1.1), diaphanes, Zürich-Berlin: 2014

[2] Ibid.

[3] Martin Clarke, ‘On Being Sessile’, The Botanical Mind, eds. Gina Buenfeld and Martin Clarke, Camden Arts Centre, Camden: 2021, 187

[4] Michael Marder, Plant Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, Columbia University Press, New York: 2013, 8

[5] Op Cit., Martin, 187

[6] Op cit., Marder, 8

THE HEROINE PAINT (WITH AMBER WALLIS)

29 JUNE TO 17 JULY 2021

The Heroine Paint, Melbourne is a joint exhibition of new and recent work by Kylie Banyard & Amber Wallis.

The exhibition follows the artists’ exhibition The Heroine Paint at Lismore Regional Gallery, curated by Kezia Geddes, current to 1 August 2021.

EXHIBITION ESSAY

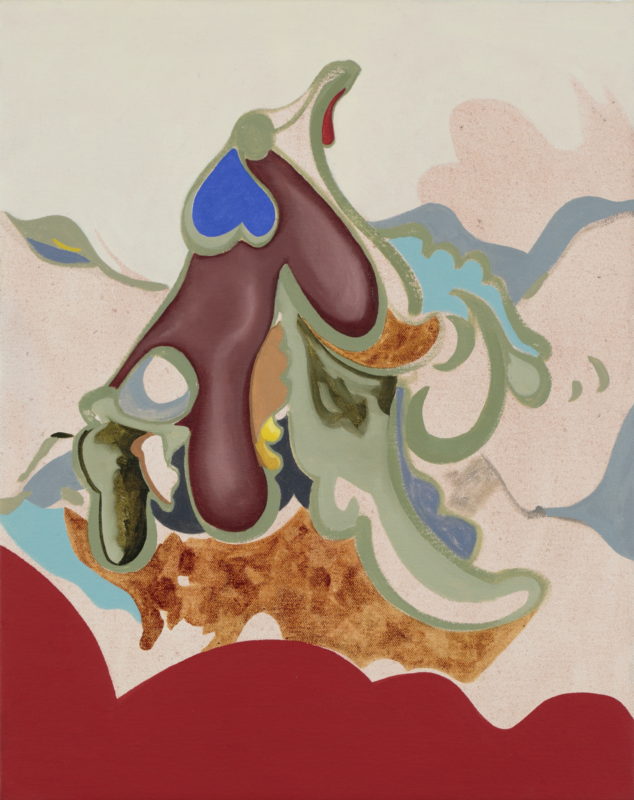

The Heroine Paint brings together the work of Kylie Banyard and Amber Wallis, highlighting their visions of painterly utopia. The artists pay homage to American Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 50s, which rejected representational norms within art and painting. Spontaneity stood at the centre of this, and a purist’s distillation of materials. The counterculture of the 1960s and 70s, which had similar aspirations to breakdown boundaries and initiate change, is also present in both artists’ work. Despite intentions for a new agenda that went with these movements, power remained largely patriarchal. Women have continued to be marginalised by this status quo. The Heroine Paint reconfigures this inequity to the advantage of women.

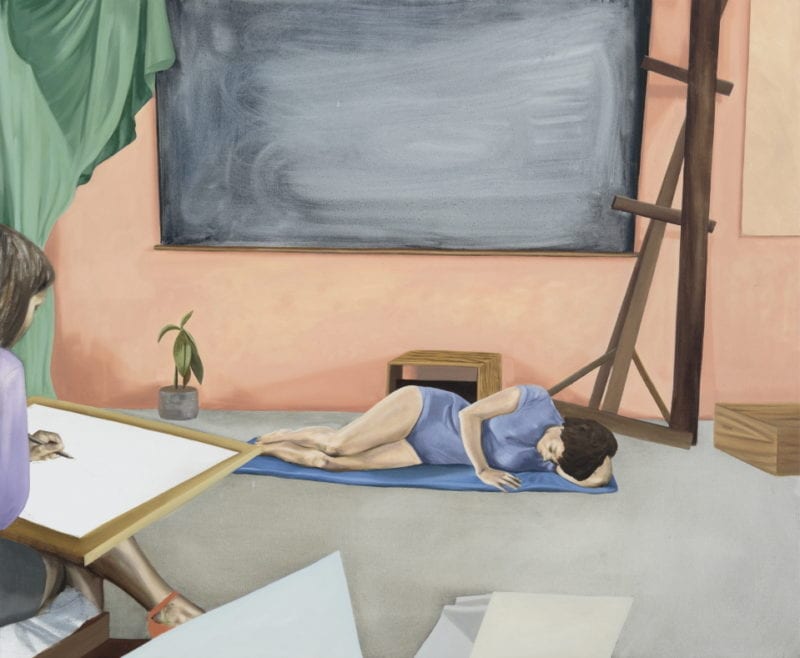

Kylie Banyard draws on Black Mountain College’s (1933-1957) photographic archive to realise lived and imagined narratives. Based in the picturesque mountains of North Carolina, the College had a non-hierarchical structure and students and teachers lived side-by-side. In addition to their education in art, design, architecture, theatre, costume, and the written word, students grew food, worked the land, cooked and ate together, and participated in construction projects. Tasks of the day were all artful and of equal importance. It was a community where art, life and education were intertwined.

Lismore Regional Gallery installation. Photograph Carl Warner

The photographic archive that Banyard has used documents what was happening at the college. It shows that women were not only present, they were active in all aspects of college life. However, as careers progressed it was evident that the art world and market still favoured men. There were female students at the school who gained recognition, and Ruth Asawa, Susan Weil and Elaine de Kooning were among them, however their reputations do not match those of the men. Josef Albers, Robert Motherwell, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning are some major names associated with Black Mountain.

In Banyard’s work, canvas (the heroic material that was used by American Abstract Expressionists as a field for colour and form and expanded to macho proportions) connects the work to the history of painting. However, the material also links to the feminine. The large spans of fabric connote the American tradition of quilting and ‘women’s craft’.

The repositioning of the historical images invites us to look towards an alternative future. Women are strong and capable protagonists, working outdoors and using their hands to make art, tend fields and build alternative futures. Banyard has long been interested in intentional communities, and she has choreographed one that presents women in ways that appear nurturing, cooperative and non-combative. In highlighting these traits that are often associated with women, she brings a shifted lens to what is valuable.

Amber Wallis is similarly drawn to reimagining the utopia to tussle real and imagined stories in paint. Although she is very much connected with the here and now, her work follows some of the principles of American Abstract Expressionism, including those of the painters of the Black Mountain School. Her art is characterised by gestural brushstrokes or mark-making, and the impression of spontaneity. Paint leads her on a journey from start to finish. It sits into the canvas, staining it like in the work of the great Abstract painter, Helen Frankenthaler. Banyard also uses this technique of staining and the two artists are drawn together by the softness this brings to their painting. The figurative stage of Banyard’s work creates a kind of stage for she and Wallis, collapsing time as though they are practicing in the period of the Black Mountain College.

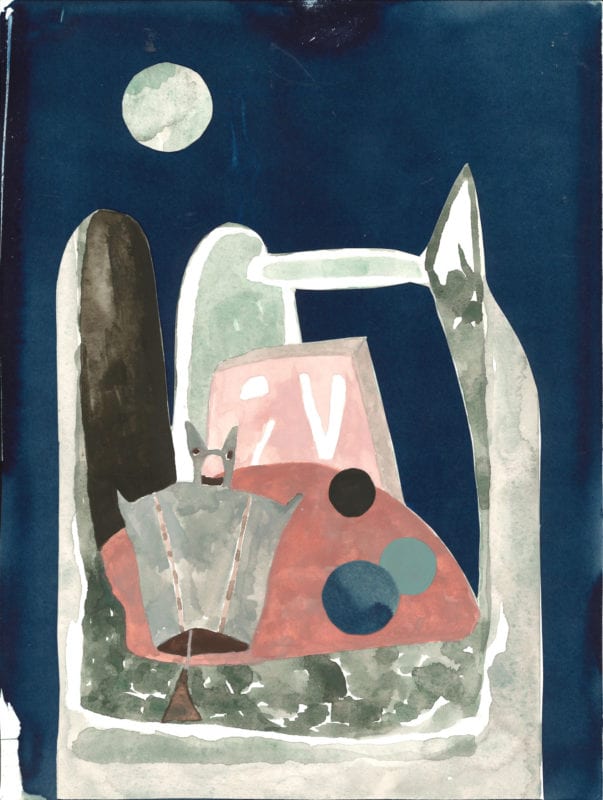

Structures from countercultural architecture often provide a framework which sets in motion a wrestle of remembering and forgetting through and in paint. As a daughter of the counterculture, Wallis’s early childhood was set on Waiheke and Great Barrier Islands in New Zealand, in hippy shacks without water or electricity. Her family grew marijuana to sell on the mainland, the Islands providing distance from mainstream society, but also from possums and goats which would otherwise eat the crops. Wallis’s paintings reference handmade houses including those from a book belonging to her father (Woodstock Handmade Houses, 1974). The book and the homes in it were projections of the life they were aiming towards. On the dark side of this utopia, Wallis and her mother left due to early childhood sexual trauma within the countercultural community, and because the freedoms and opportunities that her mother had imagined were being eroded.

Wallis’s paintings often commence with images of pornography, which initiate a call and response to mark making and erasure in order to traverse these risky beginnings. Sex is raw and exhilarating territory of titillation and drawn by a woman it throws complex light on ‘appropriateness’, and how sex speaks to empowerment and disempowerment. Imagery is obscured because there comes a point in Wallis’s mind where it is less relevant. The subject is a means into form, colour, and texture, and how they sit against one another to activate the picture. The reference material is there, however, it is pushed into the background like subconscious memories.

While women have been peripheral to the major thrust of much of art history, The Heroine Paint positions Kylie Banyard and Amber Wallis at the crescendo of their declared ‘influences and references’. The exhibition builds an alternative history and places the artists in it as current day heroines of paint.

catalogue essay for The Heroine Paint at Lismore Regional Gallery by Kezia Geddes, 2021

EXHIBITION PRESS

In response to Amber Wallis’s Women, shown at Nicholas Thompson Gallery in 2020, Amanda Maxwell wrote:

‘I’ve never seen a ghost

And won’t

Bit if I was to I know it would be the ghost of a woman

I don’t know why

Is more of a woman left?

Did she touch more?

Hold more?…’

Wallis’s paintings in this new show figure their characters in a ghostly way, too. We see women, in these compositions, through a glass; that is, through something which obscures them, absorbs them into the canvas, siphons them out of our layer of reality and into some elsewhere. In Holding Companions, 2021, for instance, washes of colour simultaneously render and obscure our titular pair – one, seemingly, a woman, the other, seemingly, a man – in a drapery of paint at once resplendently sensory and somehow immaterial. The ‘seeming’ of our pair here is important: this painting doesn’t spoon-feed us its content, or sit at a comfortable place of representational rest. Within the abstract space of the picture, the flesh of the figures shifts and moves impossibly. What is clear, and significant, is that they hold each other. This holding – this communality – is at the centre of Wallis’s and Banyard’s shared concerns.

Wallis’s earlier work has, often, been interested in sensuality, sexual desire, and the dynamics of secret-keeping and revelation. Here, however, there is a shift to thinking more about what togetherness, both in body and in spirit, can be beyond the sexual. Figures embrace, support each other, and come to define each other in gesture, shape, and colour.

Maxwell’s ghostly women ‘hold more,’ and a feminist visual poetics indeed underpins Wallis’s work about holding. For Wallis, this is accomplished in part through the reclamation of Abstract Expressionist visual vocabularies. Wallis defiantly uses the tropes of a movement which, despite its professed radicality, remained historically the domain primarily of superstar male painters – and certainly continued to exist within patriarchal art and social worlds. Wallis’s feminism is also expressed through the way that these paintings figure the self: as deeply contingent upon others, and as bound up in relationships of care and community.

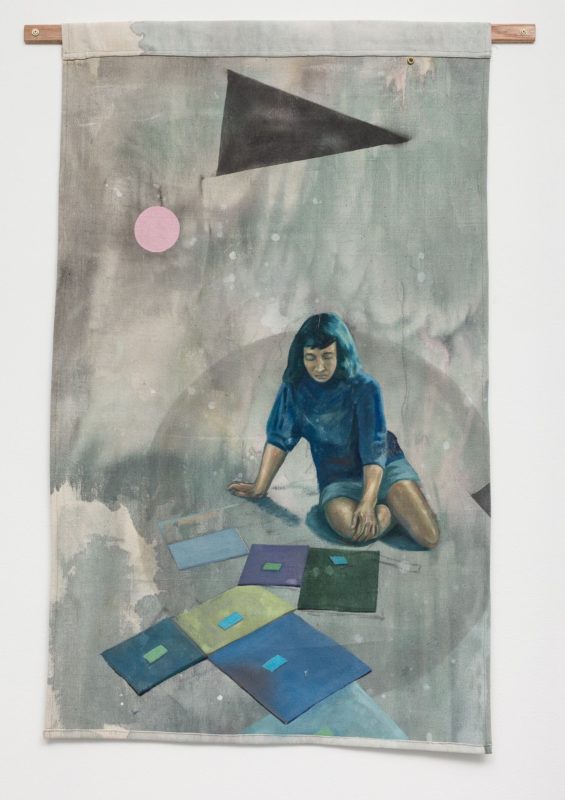

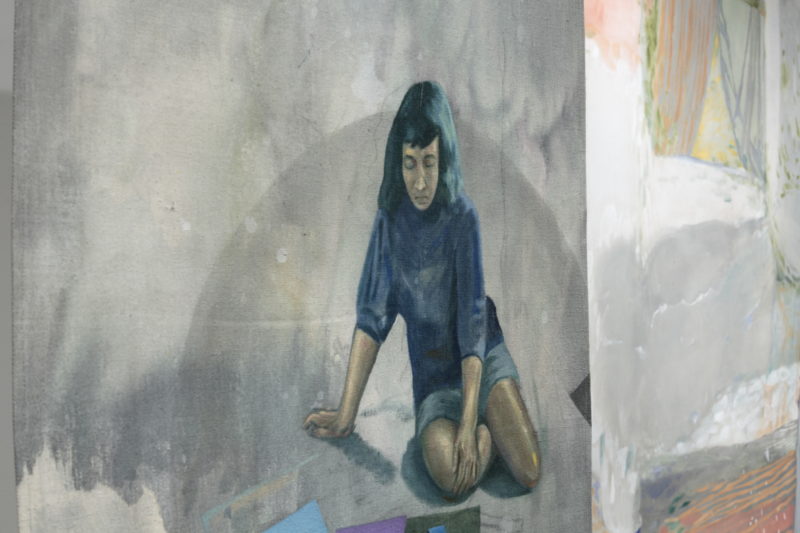

Banyard has been interested over the course of her career in finding, and telling, feminist histories. Her work in Nicholas Thompson’s ‘Holding Ground,’ 2020, like her work for the second iteration of ‘The National: New Australian Art’ in 2019, pictured the radical pedagogies of the mid-20th century American art school Black Mountain College. For these projects, Banyard drew from archival images showing pedagogical practice at the college, where women teachers and students shared moments of discovery, mutual learning, and co-creation. Here, too, was a vision – historical, rather than speculative as Wallis’s are – of women holding each other.

Banyard’s work for this latest show retains the aesthetic that was developed in ‘Holding Ground,’ picturing women at work, play, creation, and rest. In Lady Macbeth in Boone, 2018, one woman dons a crown to become Shakespeare’s feminine anti-hero, while another paints what seems – ‘seems,’ again – to be the set on which a play might take place. In these pictures, creation reiterates itself, over and over: Baynard paints a woman painting, so that another woman again can perform.

Even Banyard’s solitary subjects are creators and collaborators. Does the crown resting next to the figure in Elaine, 2017, make this woman part of the same production? Is Anni, 2017, constructing part of the same set? Attending to the connections between paintings, here, we can find in Banyard’s work not only an under-examined, utopian past, but a time more conditional, or even subjunctive.

Banyard, like Wallis, paints a world removed to some layer above (or perhaps, more rightly, rippling beneath) our own. This is a world in which we can see flashes of touch, teaching, and togetherness which are imaginative – and corrective – in a way that both encompasses and exceeds the feminism with which these artists are frequently aligned.

Artist Profile online, 28 June 2021

HOLDING GROUND

11 TO 29 NOVEMBER 2020

EXHIBITION TEXT

Holding Ground continues Kylie Banyard’s exploration of alternate models for living and learning. Her work explores and brings to a new audience the radical pedagogies of American mid-20th century art school Black Mountain College. Those pedagogies are based in practices of care for others, the development of the whole person, and care for community and environment. The paintings in this exhibition focus on a small group of archival photographs in which female artists and students are engaged in intimate exchanges and moments of co-creation, responsive to the wild mountainous land surrounding them: farming, making, reading and dancing. Banyard combines archival research with fantasy, drawing on images and ideas from the past, bringing them into the present through a painting process that conflates and overlays facets of her own domestic space and lived experience with Black Mountain College’s historical record – her paintings propose a present that is thick with remembrances of the past.

EXHIBITION REVIEW

In Kylie Banyard’s newest paintings the mood is simultaneously mystical, technicolour, strangely nostalgic and enduringly hopeful. While her latest oil and acrylic works emerged from interests in the experimental American art school Black Mountain College, which in the

mid-20th century emphasised holistic learning, this isn’t necessarily clear. Yet the aura of the influence is apparent, particularly in the most compelling paintings that depict women working together in acts of toil and farming, their skin tinged by vivid pinks and blues, blending into the environment in which they work. Existing in luminous lighting, the women’s movements are choreographed in ways that feel caring and reciprocal, not exploitative or competitive.

For an artist with a practice across many mediums, it’s clear Banyard knows painting: colours expertly morph into one another; shaded and flattened areas are designed for maximum impact; a single painting of a house is masterfully skewed, drifting on a pink background, curiously emerging as both a relic from the past and a dream of the future. Alongside the paintings are textile and sculptural forms, yet these don’t quite enhance the atmosphere the paintings so brilliantly conjure − a reverie on labour and creation, and women being with women.

Tiarney Miekus 'Galleries' in The Age Saturday 21 November, p 9 (Spectrum)

ARTIST IN CONVERSATION WITH CURATOR AND WRITER AMELIA WALLIN

THE IMPROBABLE OUTSIDE

28 FEBRUARY TO 18 MARCH

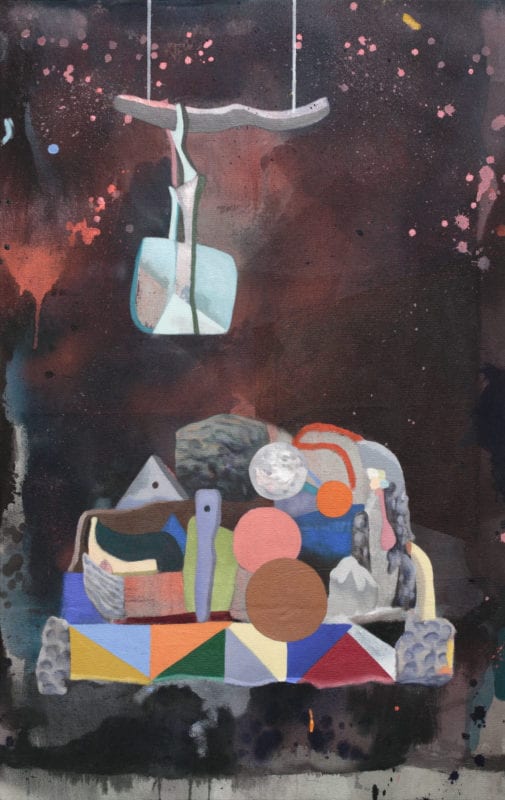

EXHIBITION PREVIEW

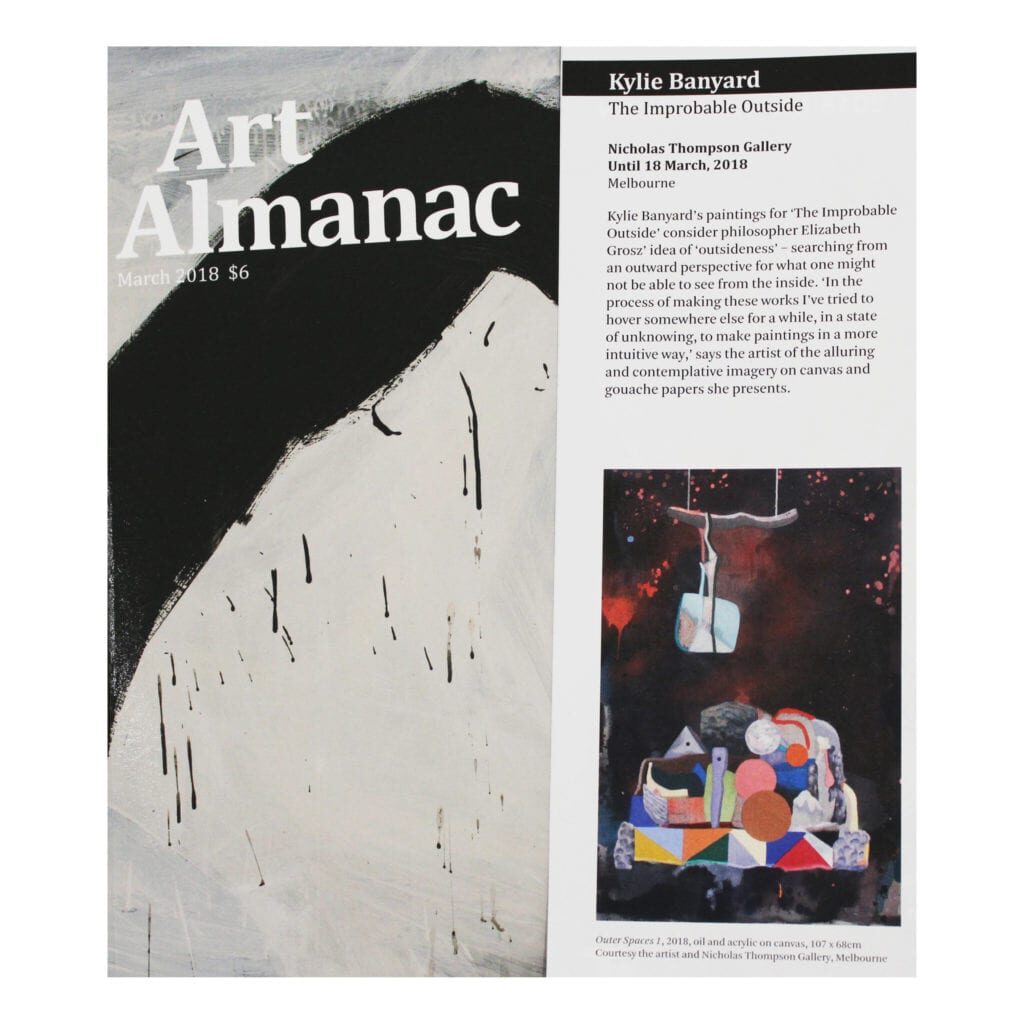

In the introduction of Architecture from the Outside Elizabeth Grosz refers to the outside as "the place one can never occupy fully or completely, for it is always other, different, at a distance from where one is." (Grosz, 2000, p.16) She talks about the unexpected and liberating joy of "outsideness" as being able to see what one might not be able to see from the inside. Grosz's proposition is not particularly comforting or reassuring, but it is alluring and it appeals to the utopian imaginary. This group of paintings occupies an affectual reckoning of Grosz's "outsideness". In the process of making these works I've tried to hover somewhere else for a while, in a state of unknowing, to make paintings in a more intuitive way. There are associations with works I've made in the past but the connections are casual and have become obscured.

EXHIBITION PRESS Link to Art Almanac Exhibition Preview here

NEWS

KYLIE BANYARD INTERVIEWED ON RADIO NATIONAL ‘THE ART SHOW’ ON THE NATIONAL, SYDNEY

Kylie Banyard interviewed by ABC Radio National’s ‘The Art Show’ today on the artist’s fascination with idealised ways of living and her latest artworks, showing at The National in Sydney . Kylie Banyard’s work is exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia as part of ‘The National 2019: New Australian Art’ – a presentation…

KYLIE BANYARD ANNOUNCED AS EXHIBITING ARTIST IN ‘THE NATIONAL 2019: NEW AUSTRALIAN ART’ AT MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, SYDNEY

The Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Carriageworks and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) today announced that The National 2019: New Australian Art will present the work of 65 emerging, mid-career and established Australian contemporary artists living across the country and abroad. A major collaborative venture, The National 2019 is the second…

KYLIE BANYARD DISCUSSES DANA SCHUTZ’S ‘BREASTFEEDING’ WITH ART GUIDE

Five on Five: Kylie Banyard on Dana Schutz’s Breastfeeding In this first series of Five on Five we’re asking five painters to speak about a painting that has influenced, inspired or resonated with them. In this episode Kylie Banyard reflects on Breastfeeding (2015) by American artist Dana Schutz. As you listen, you can see in the painting (reproduced above) that Banyard is captivated…

KYLIE BANYARD EXHIBITION PREVIEWED IN ART ALMANAC

Kylie Banyard: The Improbable Outside 28 February 2018 | Art Almanac Kylie Banyard’s paintings for ‘The Improbable Outside’ consider philosopher Elizabeth Grosz’ idea of ‘outsideness’ – searching from an outward perspective for what one might not be able to see from the inside. ‘In the process of making these works I’ve tried to hover somewhere…

- « Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3