ANTONIA SELLBACH

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Antonia Sellbach has held exhibitions in Victoria and Tasmania since 2010, including solo exhibitions at Heide Museum of Modern Art (2016-17), Schoolhouse Gallery (2022), BUS Projects (2015), C3 Contemporary Art Space (2014) and Faculty Gallery, RMIT (2011). Her work has been included in group exhibitions at the National Gallery of Victoria; RMIT Gallery, Melbourne; La Trobe Art Institute, Bendigo; SVPA Gallery, University of Tasmania, Launceston; M16 Artspace, Canberra; Counihan Gallery, Melbourne and Bundoora Homestead Art Gallery, Bundoora. Sellbach’s work is held in prominent private and institutional collections including Artbank, RMIT University and La Trobe University.

Sellbach has a practice-led PhD from University of Tasmania, an MA (Research) Fine Art and a BA (Hons 1) Fine Art from RMIT University, Melbourne. She has taught at RMIT and Melbourne Polytechnic and has led workshops at the National Gallery of Victoria (2018) and Heide Museum of Modern Art (2016-17). Sellbach’s work has been featured in The Age, Art Collector, Belle, Vogue Italia, Inside, Est Magazine and Primer Magazine.

ARTIST CV

DOWNLOAD PDF

WORKS

CONTACT GALLERY FOR PRICE INFORMATION

PAST EXHIBITIONS

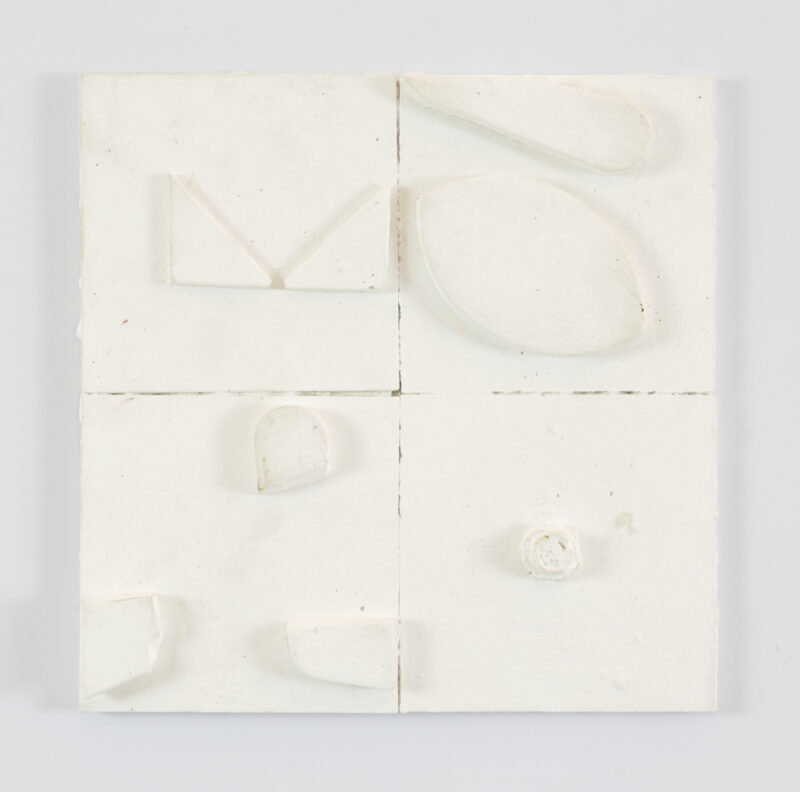

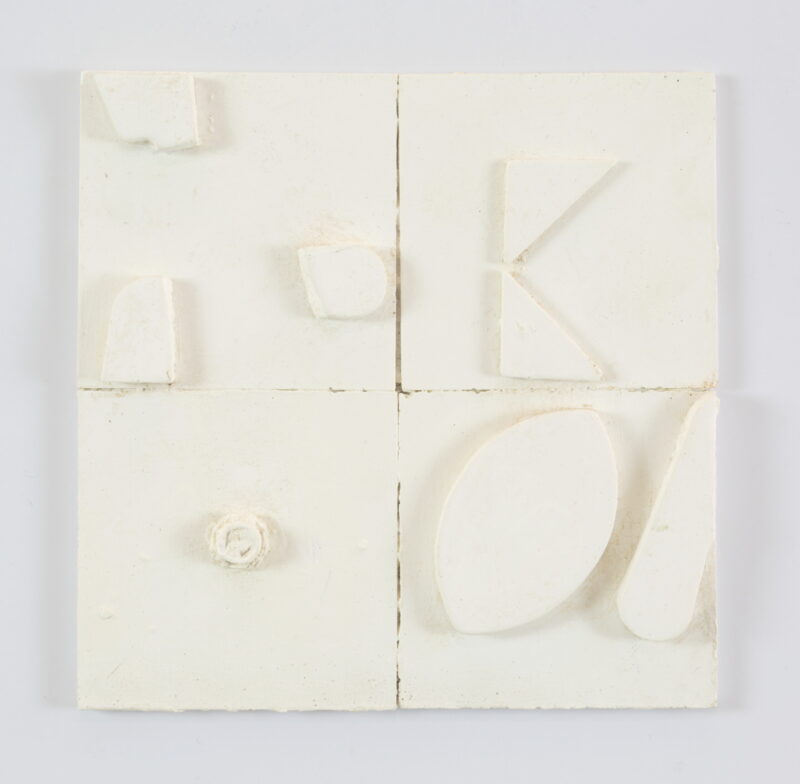

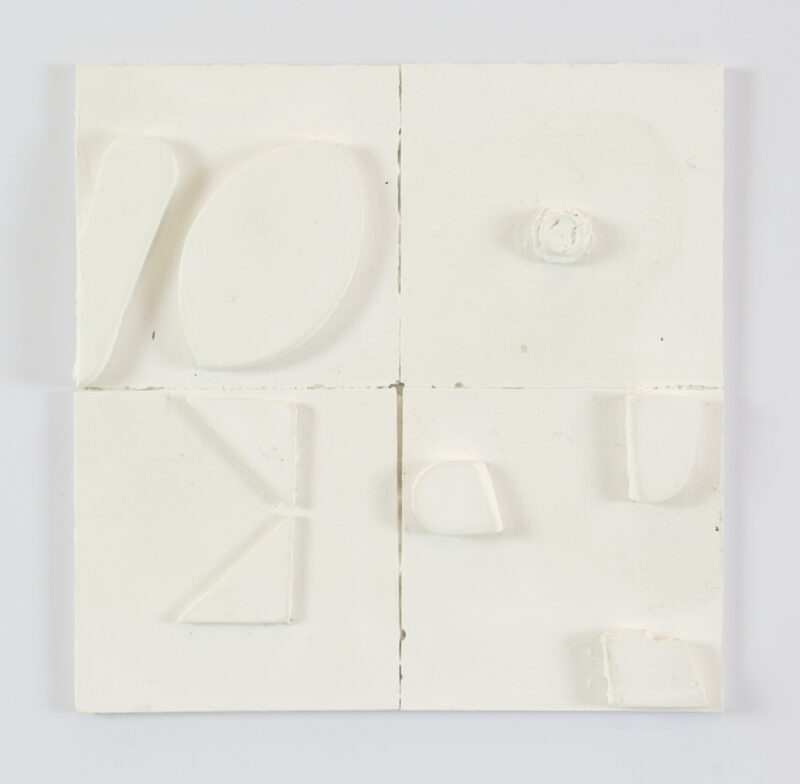

DOTS AND ARCS (THE MONOCHROMES)

24 MAY TO 10 JUNE 2023

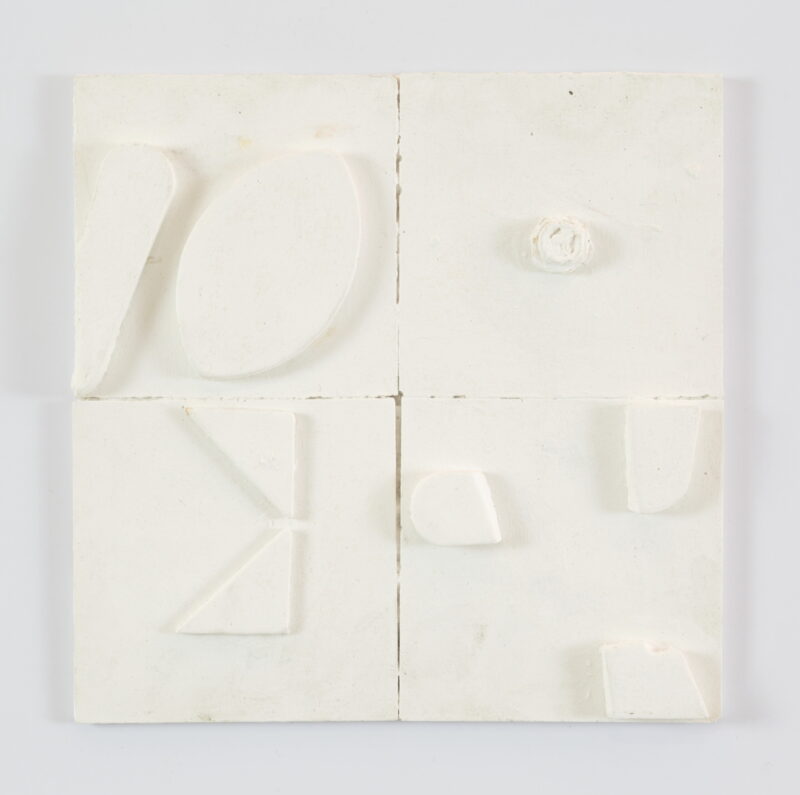

Within this series monochrome dots, arcs and ellipses emerge, populate and reproduce into an intuitive system of parts.

Dots and Arcs (the monochromes) initiates a counterpoint to the previous ‘Unstable Object Series’. The latter was preoccupied with a system of addition and subtraction of straight beams, a process of ‘building (and dismantling) through painting’ (Sellbach, 2021) and a focus on the tensions that exist in and around the depiction of boundaries and frames. The series Dots and Arcs provides a prompt to explore a more organic system of parts. The work remains rule-based, iterative and serial, and yet there is an intuitive breaking of the depiction of grids in order to explore new forms of visual and conceptual production.

Dots and Arcs provides a new framework, a growing ecosystem of forms that begs the question: how do organic structures inform systems of building? Dots and Arcs are indeed more emotive and less architectural. We can build structures piece by piece, but what other systems of building are there? This series nudges us towards the internal, emotional geometries of feeling, the building blocks and composite parts of the internal world.

In Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations he proposes an open ended, radical approach to meaning making which is helpful here:

‘You can think now of this, now of this, as you look at it, can regard it now as this, now as this, and then you will see it now this way, now this...’ (2009, p.211). Wittgenstein’s iterative approach is useful to take with this series, where each potential association adds to a layered composite and a growing meaning.

The segmented geometric parts and forms of Dots and Arcs relate at times to the mechanical (propellers, machine parts, cogs, keyholes) the organic (seeds, plants, petals) the micro and internal (amoebas, particles, cells) the macro and cosmological (planets, moons, stars), and yet they are none of these in any complete sense. There is a defiant quality, a ‘state of unfolding’ or emergence, a series of moments, an invitation to sit in the uncertainty of chaos, to listen for the quiet noise of new beginnings, an unfurling of new systems and ideas in orbit.

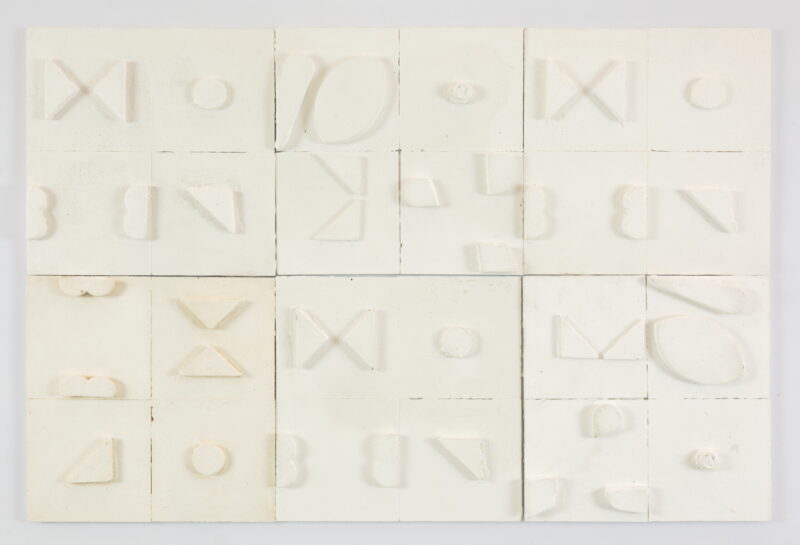

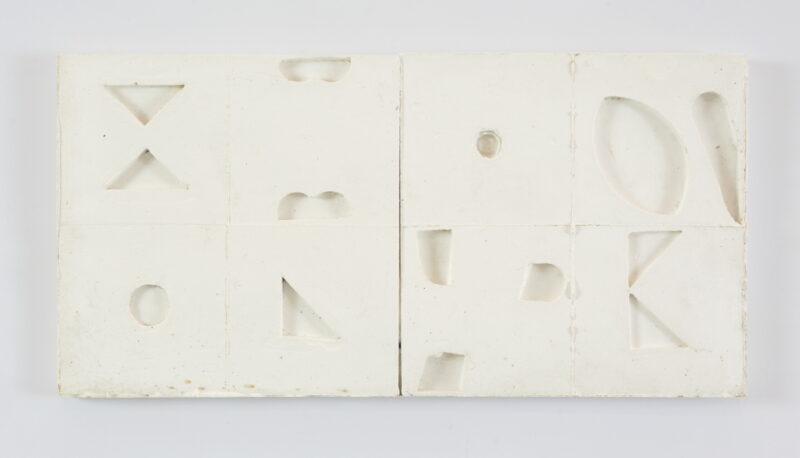

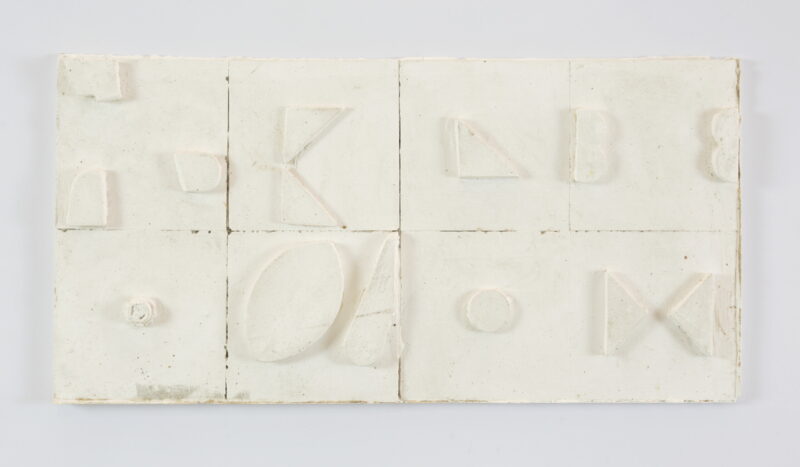

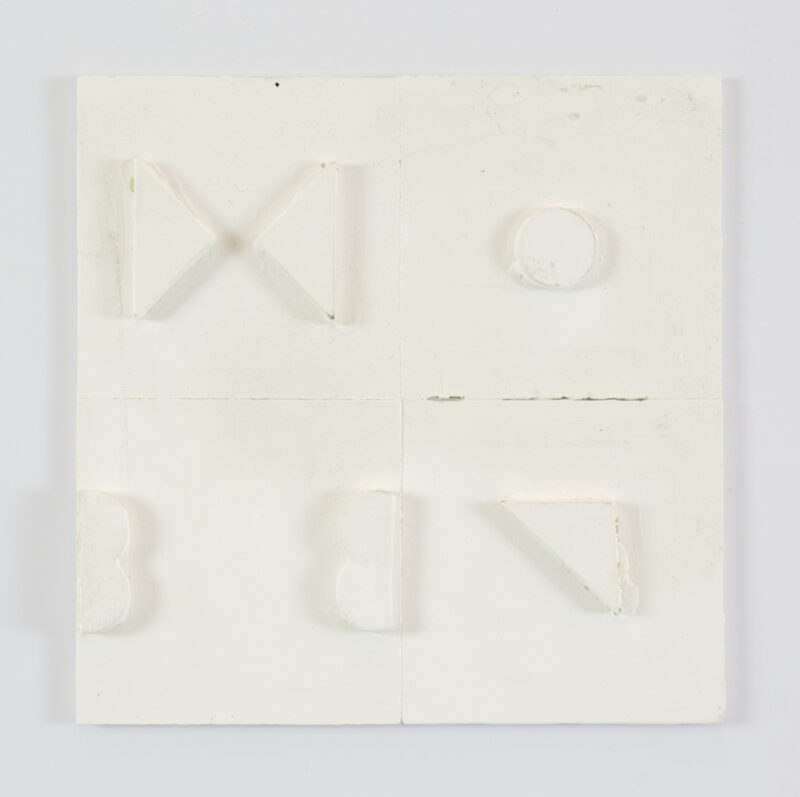

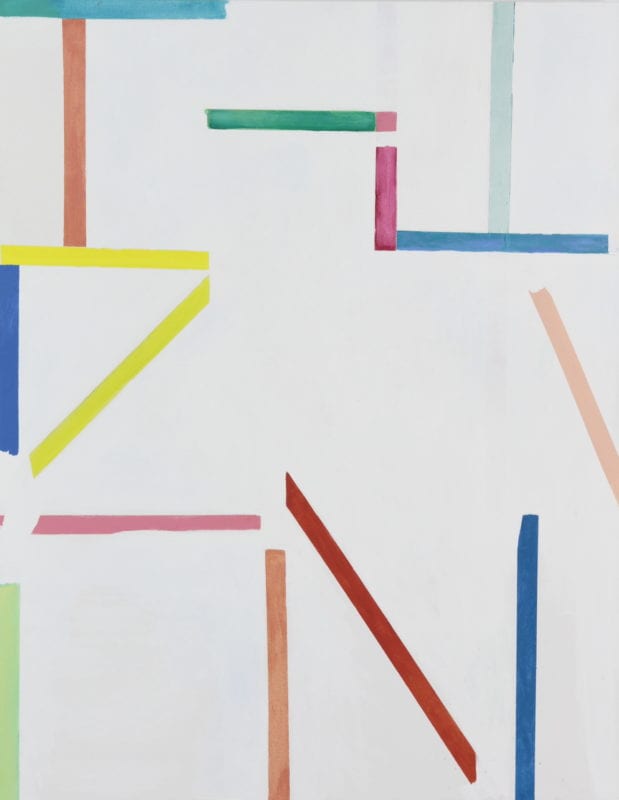

TO BUILD AND DISMANTLE

9 TO 27 MARCH 2021

EXHIBITION ESSAY

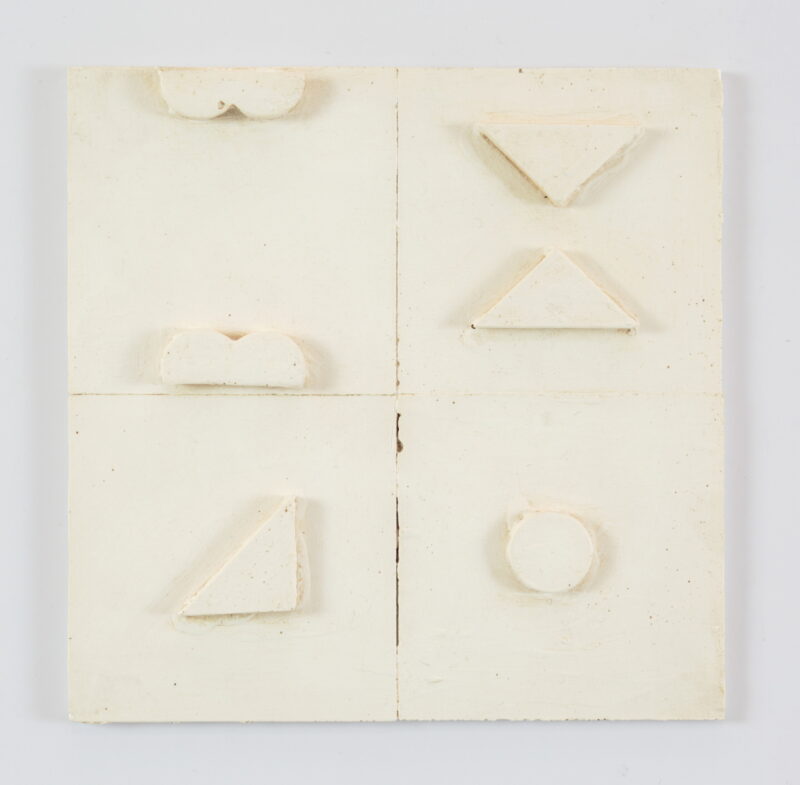

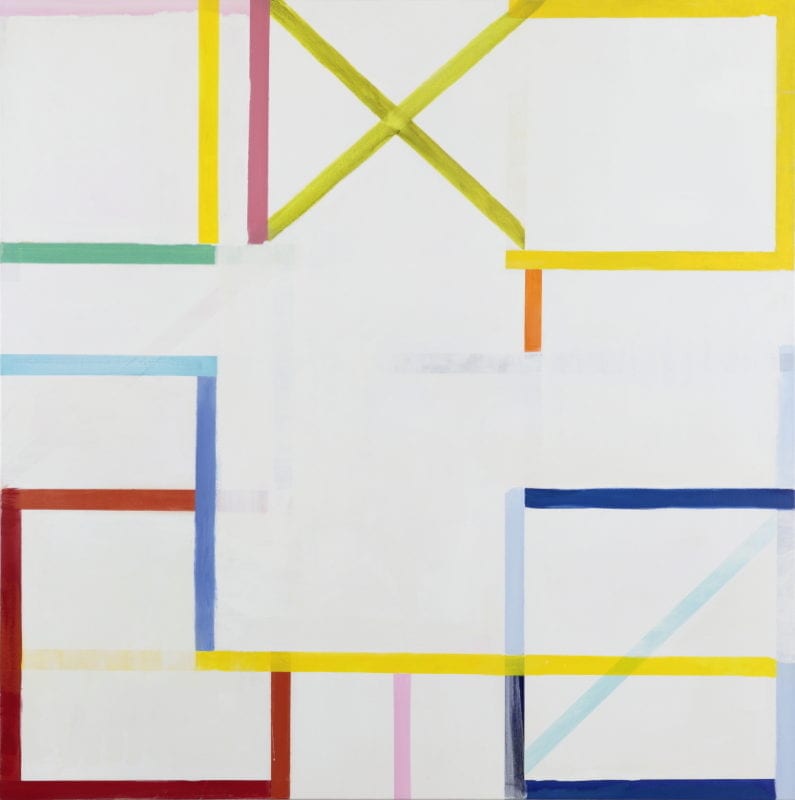

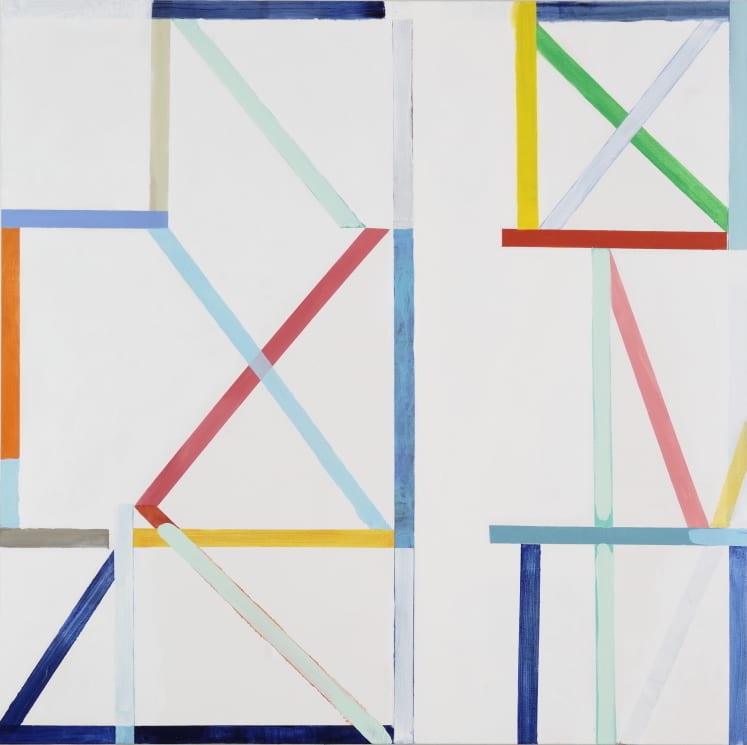

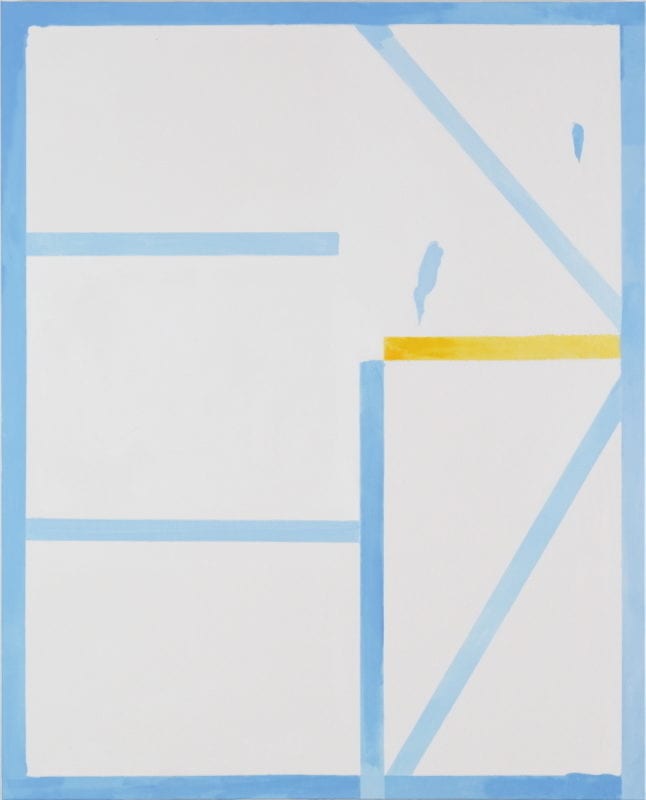

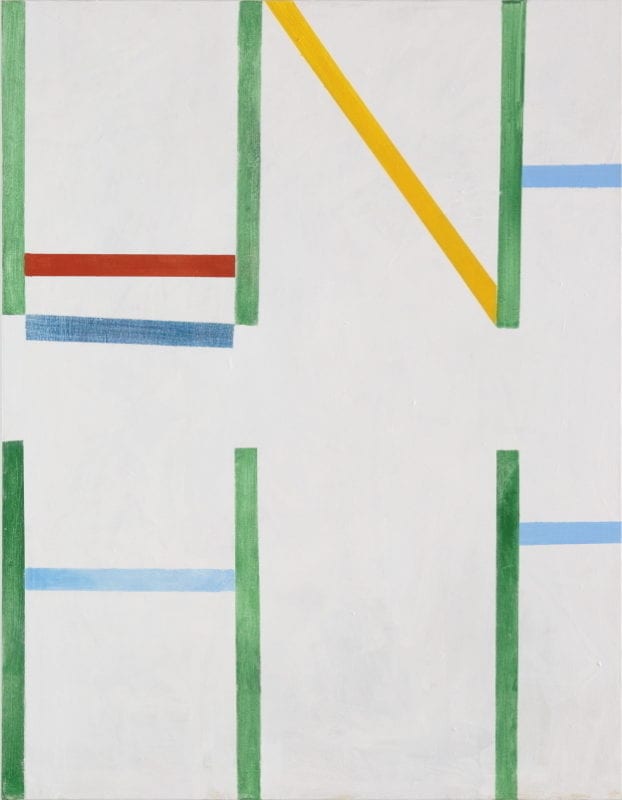

Something is happening in the bones of Antonia Sellbach’s house. For years she has reliably “built” her canvases out of thick, constructed lines (“beams”) that are roughly 4.5 centimetres in width. According to the artist, the beams are “never measured, but endlessly repeated through bodily memory and estimation”. This beam-architecture was never oppressive. It was light and jewel-toned, with thick lines arranged and rearranged to form an intuitive lattice. Sellbach has previously described this process as a form of play, a process that she relates to moving building-blocks. In this way her practice has been suspended half-way between an abstraction of work (as a ‘builder’) and a performance of improvisation.

In the past, while Sellbach’s beam-architecture was never sturdy, the artist worked with grids of satisfying tension. In earlier paintings these beams were always playful, constantly rearranged and tumbled by the artist, as she would often rotate them to discover new strains and pressures. In ‘To Build and Dismantle’ a shift has occurred, and the architecture of Sellbach’s new paintings no longer wish to support themselves. It is a momentous expansion of the artist’s guiding principles.

“I held on to the straight beams for a long time, to see what they could teach me”, says Sellbach. It is time now, however, for some cracks to appear. Sellbach has painted great chunks, arcs and gaps into her once-straight beams. Sometimes the absences seem like cleanly, carved bites, other times they are more organic breakages. The white paint that the artist has always used as a supportive field is tearing and warping into the colourful beams. Especially when thinking of Sellbach’s previous canvases, the intrusion of the white background seems like a form of destruction. Imagine placing an older work series beside these new paintings and you can appreciate the distinct sense of disintegration. Yet the artist has always subtly refused the neurotic logic of hard-edge cleanliness. The equation of whole shapes equalling pure art has never appealed to her. When asked if subtracting areas from her beams felt too destructive, Sellbach countered with her own question, “is a natural process of erosion also a building process?”

The background and foreground of Sellbach’s paintings have never been so complicated, so conflated. The artist speaks of seeing sections folded over other sections, as if the work is collapsing (or, conversely, getting stronger, getting more re-enforced). Always beautiful, Sellbach’s version of white is particularly assertive here. As in her past series, layered beneath the white is pentimenti of painted over beams, faint stripes of almost-unwanted beams. The artist has always insisted that her white-space not be thought of as ‘empty’ – gaps and spaces are instead active, and therefore integral. But for the first time this significance is dictating the space. It is a shift akin to moving from the drawing of a blueprint towards a drawing of ‘blue’. While the changes in her process never occur suddenly, Sellbach progresses forwards and backwards through the layers of her paintings, “thinking and painting, and thinking through painting and thinking about painting."

So, what is left of the beams that Sellbach has honoured for so long? Some of them are torn to shreds, ribbons of their former selves. They have movement that the artist attributes to a shift in thinking. Perhaps they are the shadows cast by beams she has once built? Perhaps the colours on these canvases are reflections or refractions of light. They refer to building material, i.e. treated pine planks, but then why do some lines appear to be, miraculously, still growing? Sellbach is open to what her painted beams might be building, what they might depict structurally. But this exhibition takes that ambiguity to new lyrical heights.

The opportunity that this recent direction provides seems endless – and the artist is extremely fond of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s generative quote “You can think now of this, now of this, as you look at it, can regard it now as this, now as this, and then you will see it now this way, now this...”. However, Sellbach’s logic is not incessantly fluctuating, it too (like the beams of her architecture) has a certain rigidity. The title of this exhibition refers to the metaphorical structures being built and dismantled in her paintings, but also to the systems that assist her. While laws of limitation and repetition have served her well, it is time for new values. To break is to build. In Sellbach’s own, typically mirrored language, there are two opposing behaviours here: “There's a slow undoing... some new rules slipping in.”

VICTORIA PERIN

FRAME WORKS

3 TO 21 JULY 2019

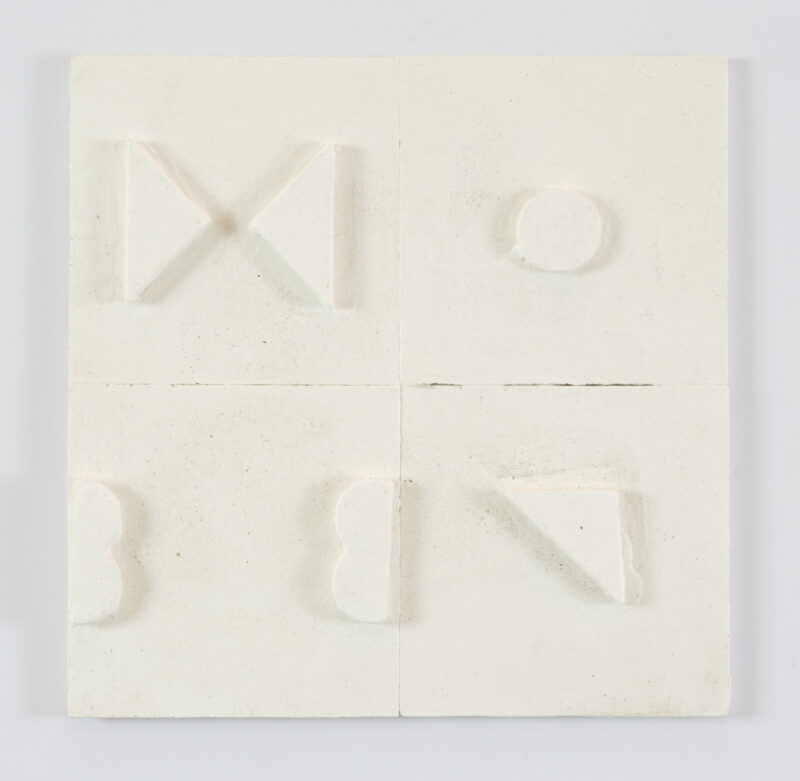

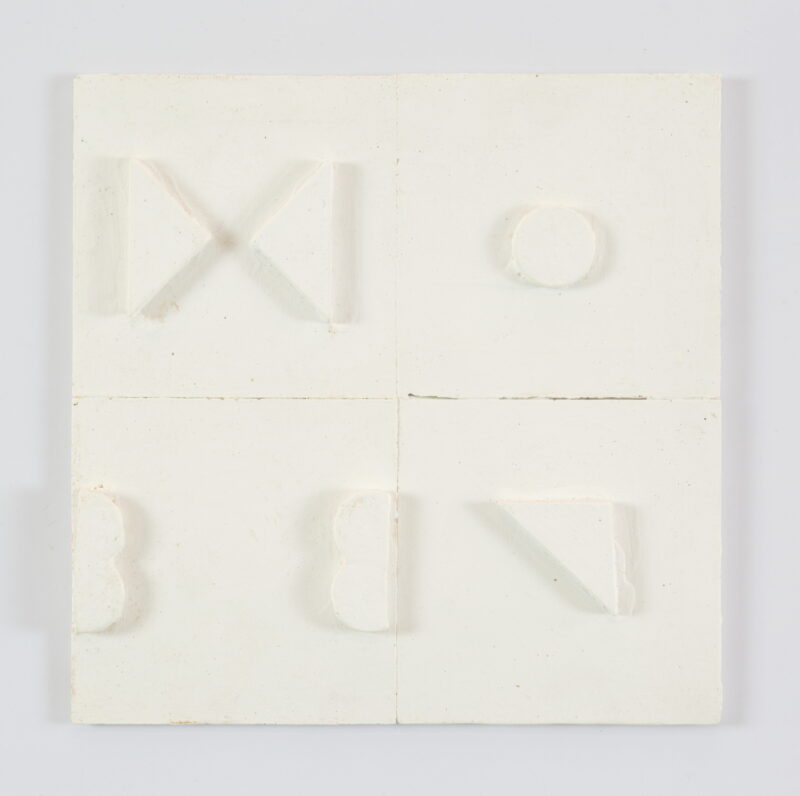

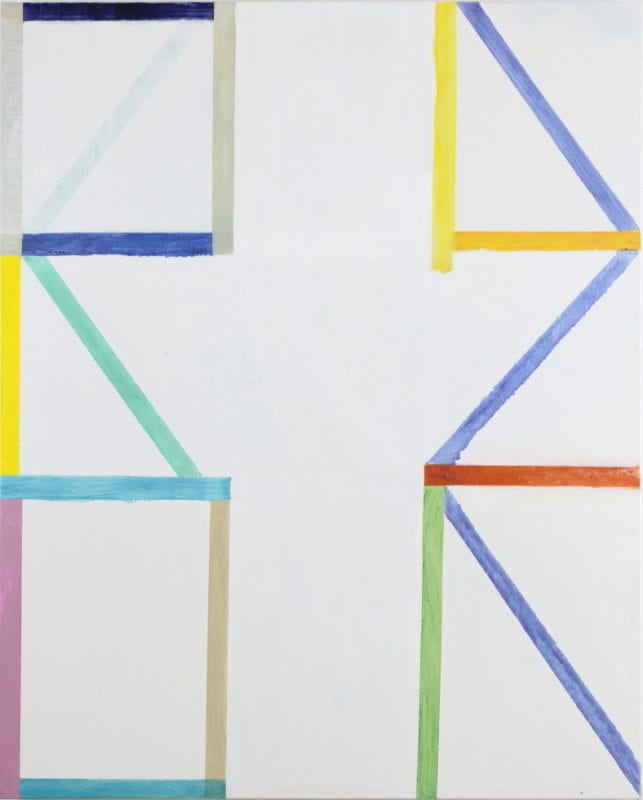

Antonia Sellbach's work explores the depiction of coloured, serial frames which in their various iterations, expand and contract, and construct and deconstruct. The forms they create allow us to grapple with how we read meaning through an abstract image, the logic of what, where and why. For Sellbach, the repetition of limited forms allows for a language to emerge and it is within this syntax that abstract connections are made.

[FRAME. MID. CRUX]

Upon reflecting the difficulties of translating the French author Hélène Cixous’ first book Tombe into English, Laurent Milesi[1] explains his use of formal punctuation in assisting the reader toward a more faithful picture of the original text. As an ‘infinite orchestration of ever-recombining motifs’[2] and a labyrinth of literary and sonic experimentation, Milesi approaches the text—newly Tomb(e) in English—using square brackets to offer explanatory notes and to alert the reader to the text’s ‘original cruxes’: the essence of what otherwise gets ‘lost in translation’.

Antonia Sellbach’s latest body of paintings from the Unstable Objects series takes heed of such a task. In these works—which form the final material outcome of a series of exhibitions as part of her practice-led PhD—we find an (in)formal infrastructure that is analogous in paint to that of Milesi’s brackets. In returning to an original interest in (and subsequent dissociation from) the frugal celebrations of German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher’s rectilinear Framework Houses (1959–1971), Sellbach creates her particular grammar of abstraction through the presence of transgressive ‘framing’ or ‘edge’ works within the paintings’ broader fields of relation.

In acknowledging paintings as zones of interaction between various actants, we can read Sellbach’s process as one of triangulation. The artist’s hand—in concert with a disciplined, cognitive drift [Dérive[4]] through operations of serial decision-making—is mediated through the application of a limited (by design) but potentially endless (by application) framing apparatus: a series of 3.5cm wide, rectilinear timber struts that function as visualisation props to anticipate particular ‘moves’ in the form of a commitment to paint on canvas. Applied as if engaging a processual game of jenga, or an experimental mathematics homework exercise, these narrow colour fields are built up to be subsequently, partially undone within no more than two additional moves; they are made visible and then either entirely or partially obscured as if plays of ‘addition’ and ‘subtraction’ ad infinitum until a certain equilibrium has been achieved. In giving form to these marks as a lexicon is to a language, this three-tiered negotiation process is what Sellbach considers to be the ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘maybe’ logic of the works’ fundamental gestural advances.

These paintings are redolent of other framing apparatuses present in the world around us: the often obscured architectural scaffolding that allows an architectural structure into being; leaky linguistic categories that work to both contain and defy expressions of our identity; and this very exhibition as a mode of framing (by namesake and function) a much larger series of indeterminate, processual objects. Important to understand is that these paintings contain opaque fields of block-colour to both support (as in ‘prop up’) and demarcate (as in ‘mark out’) a series of middle-ground propositions that are central to the terrain of their ontology. As with Milesi’s brackets, the presence of Sellbach’s coloured struts function to offer a sense of before and after, of foreground and background and of a potential primary and ancillary text. Such an apparent, non-linear approach to the paintings’ own history of production is what the artist refers to as a chronology of ‘imagined timelines’: the perception of temporal frameworks that might ‘stack vertically, or loop and repeat’ to destabilise the notion of a ‘pure start or end point within both research and practice’.[5]

It is in marking out this terrain so evidently, yet with no clear pathway as to where we are being persuaded to read the stress as falling, that Sellbach reinforces the game-like qualities of these works. Is the artist, for example, asking us to focus in or around these highly keyed frames as brackets? Or, are we rather being encouraged towards a polysemous reading in and across and between, or even in negation of, the anti-restraint of their attendance?

An instinctive reading would return to us the opaque areas as fortified and confident (leaping forward), with the mid-ground, milky white fields being in a state of vulnerable, near-absent ambivalence (receding away from us). As if prompts from an afterlife (but actually from a before time), there is a tendency to seek out ghostly residuals of these marks; they are a kind of ‘sous rature’—what Martin Heidegger refers to as the philosophical strategy of legibly crossing out words—as if a game of hide and seek, signalling to us that there is more to this vocabulary than first meets the eye.

The uncertainty of such prompts is what is most at play in these works, and, I would argue, what is most interesting about processes of translation—whether between differently spoken writers or in the formulating of a visual language between an artist and her audience. It is the crux, to borrow Milesi’s own figuration, that is being bracketed off as a means of relating back into the essence of what these paintings are suggesting to us: that the simultaneous, partial concealment and leaking of a middle-ground proposition that is present but not fully formed, that is blurry and edged but not hard-edged, is precisely where the stuff of life resides.

Abbra Kotlarczyk

is an artist, writer, editor and sometimes curator based in Naarm/Melbourne.

[1] Hélène Cixous, 2014, Tomb(e), (Trans. Laurent Milesi), Seagull Books, p. viii.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] The French translation of ‘drift’ here references Guy Debord’s 1956 Theory of the Dérive in which he proposed the Dérive as a mode of unplanned travel through a landscape (notably an urban one) in attainment of more free and objective encounters with the terrain. By situating this translation in apropos to Sellbach’s painterly process, there is a sense in which her own tendency to drift can be explained by such simultaneously intuitive and yet limited forms of ‘moving through’.

[5] from Antonia Sellbach email correspondence, June 2019.

NEWS

- « Previous

- 1

- 2